Translator Shelley Fairweather-Vega is preparing an anthology of new women’s writing from Kazakhstan with support from a RusTrans bursary. Here she talks about the translation issues involved in making a largely unknown ‘small’ literature appeal to Anglophone readers and publishers, and how she dealt with them in her version of ‘Aslan’s Bride’, a short story by Kazakhstani author Nadezhda Chernova. You can read part of ‘Aslan’s Bride’ here.

Translating foreignness and folksiness in Aslan’s Bride

We translators are supposed to make the foreign more familiar. This is true whether we prefer to domesticate or foreignize when translating, whether we explain all aspects of the text to its new readers or leave multiple semantic and stylistic mysteries for them to consider. Even the most literal translation cannot help but make the original text more intelligible, however slightly, to readers in the new language – the mere act of using familiar words, a familiar alphabet, makes the foreign text that much more understandable, moving it from the realm of the completely incomprehensible to the realm of what could possibly be comprehended.

We translators are supposed to make the foreign more familiar. This is true whether we prefer to domesticate or foreignize when translating, whether we explain all aspects of the text to its new readers or leave multiple semantic and stylistic mysteries for them to consider. Even the most literal translation cannot help but make the original text more intelligible, however slightly, to readers in the new language – the mere act of using familiar words, a familiar alphabet, makes the foreign text that much more understandable, moving it from the realm of the completely incomprehensible to the realm of what could possibly be comprehended.

Yet occasionally we come across a story that purposefully resists our attempts to drag it into familiarity. Some writing is intentionally surreal or nonsensical, of course. But some, like Nadezhda Chernova’s “Aslan’s Bride,” uses the most commonplace, colloquial language possible, and nevertheless places foreignness center stage, forcing characters and narrators to grapple with the unknown. Translating this story, then, presented me with an unusual task: preserve the aura of both folksiness and foreignness, and make sure the characters’ own sense of estrangement reaches target-language audiences intact.

Nadezhda Chernova

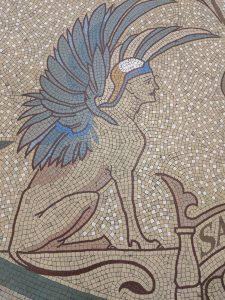

Ossetian woman

Chernova is a Russian writer who has had a long and successful career in Kazakhstan, and is well-placed to tell stories that span the multi-ethnic space and painful history of that country. I was introduced to her work by Zaure Batayeva, a Kazakh writer and translator, who is collaborating with me on Amanat, our anthology of recent Kazakh women’s writing that is just about complete. Amanat is a Kazakh word meaning ‘sacred trust’, and “Aslan’s Bride” is one of the highlights of this collection. In the story, a hapless young woman with the Russian nickname “Milochka” – “Sweetie,” maybe, though I decided not to translate it into English – leaves her loveless world behind and sets out to points unknown. What she finds is a strange village by a beautiful sea, where the women all wear black and speak a different language (in other words, they’re as incomprehensible to Milochka as an untranslated text!), and where, thirty years after the end of World War II, one woman, Tomiko, is still expecting her son Aslan to return from the front lines.

Presented here is the first part of the long short story, accounting for about 30% of the full text. The foreignness in the storytelling is not immediately apparent. On the contrary, our introduction to Milochka is unremarkable almost to the point of dullness; she is “not a pretty girl” in an unnamed, uninspiring city, working in a library and clinging desperately to a terrible love affair. The narrator, channeling Milochka’s own thoughts, speaks in naïve (but rather sweet) clichés. In translating this portrayal of Milochka’s drab life, it was important to retain all the naivete of Milochka’s thinking, all her quiet desperation. And so I replicate Chernova’s use of clichés (“her heart would burst from her chest in happiness”), occasionally altered slightly (“She bided her time, but her time just wouldn’t come”). And I tried to keep the English as casual and innocent as possible, too, down to the matter-of-factness in the way Styopa’s death is announced, and the simple way in which Milochka cries at his grave (“for a while”).

Readers’ first clue that there is more to the world is Milochka’s discussion with her cynical neighbor, Antonina, about geography. Milochka wonders if she should go north to find a husband. Antonina dismisses the idea: “Nonsense! Anyone who can’t get married here won’t have any luck up there. Maybe someone would amuse himself with you a while, dabble a bit, a month maybe, and then—whoosh! They’ve all got lawfully wedded wives sitting down south, waiting for their men to come back rich.” Now we know Milochka is living her life in an in-between place, neither north nor south, across which people travel to make their fortunes. And yet, given that the Milochka we meet in the first couple pages is not one to take charge of her own fate, we are still surprised when we learn of her sudden departure into the unknown.

Where does she end up? This is somewhat of a mystery, both in the original and – intentionally – in translation. There are clues, such as the discussion of north and south already mentioned, and Milochka’s thoughts about explorers who cross “the Gobi Desert and the Asiatic steppe and the winter forests of Old Rus’,” and if we know that Chernova is a Kazakhstani writer, we can assume the warm sea Milochka reaches is the Caspian Sea. But who are the somber people she meets there? Again, there are clues, which may or may not be intelligible to the story’s original readers, and certainly less so to us reading in English. The people speak a different language and have strange (non-Russian and non-Kazakh) names: Costa, Tomiko, Aslan. In a poster, Stalin’s mother looks like one of the local women, who dress in all black. I puzzled over those clues while translating, but did not have a good answer until I consulted with Zaure. Her theory is that Milochka stumbled upon a community of Ossetians living on the Caspian Sea, a generation after being deported there by the autocrat in Costa’s poster. To the Soviets, and indeed to the czars before them, remote and underpopulated Kazakhstan seemed the perfect place to send undesirable individuals and groups. A long list of ethnic communities, including many from the Caucasus, were deported there during and after the Second World War. Kazakhstan reported a population of about 4,000 Ossetians as late as a 1989 census. So this theory is a good one.

To Milochka, however, the name of the place she has moved to, and the origins of the people there, are of no real interest. The only thought she articulates to herself on meeting Costa is “What a sloppy old slob!” as she giggles at his clothing and the size of his nose. The original and the translation both persist with Milochka’s idiomatic framing of everything around her, including the descriptions of what otherwise might have been portrayed as exotic foreign characters. For instance, later in the story, we’re told in quite familiar terms that “Tomiko was all business” and “Costa went around sighing over Tomiko,” and they eat berries from a bush or tree whose Russian name, кизил, covers a genus of over 80 diverse species on three continents. My search for an appropriately vague and folksy name for that berry landed on “houndberries.” Does it matter, either to Milochka or to us readers, what exact type they are?

The approach I embraced as I completed this translation is to simply preserve these mysteries, letting English-language readers wonder about everything from the houndberries to Tomiko’s language. In this modern-day Kazakhstani fairy tale, we don’t need to know the name of the city or the sea, or why people have the names that they have, any more than we need that information in a tale from the Brothers Grimm. I admit this approach has backfired – one literary journal rejected “Aslan’s Bride,” citing its length but also the editorial board’s difficulty placing the story in time. The year, however, is the one detail that is specified with certainty in the text. This leaves me to wonder if the editors’ real disorientation was in space, not time. That is an understandable response. It’s also exactly the response I want this translation to provoke, and celebrate.

“Aslan’s Bride” is part of a planned anthology of contemporary women’s writing from Kazakhstan, collected and translated by Zaure Batayeva and Shelley Fairweather-Vega and financially supported in part by RusTrans. Final arrangements with a publisher are pending, but you can learn more about the anthology and individual stories by contacting Shelley at translation@fairvega.com. Read an extract here.

lonely bike shed, to flipping a Waiting for Godot-esque story on its head when we discover (many pages in) that the protagonists are in fact broiler chickens on a meat farm, Pelevin has proved himself to be one of the most restless experimenters in literature today and a master of bending narrative forms. When Viktoria Malik, my co-translator, and I read his 2017 novel iPhuck 10, we knew that he had somehow managed to take things one step further. We were hooked, and felt we had to bring this bizarre and wonderful creation to a broader readership around the world.

lonely bike shed, to flipping a Waiting for Godot-esque story on its head when we discover (many pages in) that the protagonists are in fact broiler chickens on a meat farm, Pelevin has proved himself to be one of the most restless experimenters in literature today and a master of bending narrative forms. When Viktoria Malik, my co-translator, and I read his 2017 novel iPhuck 10, we knew that he had somehow managed to take things one step further. We were hooked, and felt we had to bring this bizarre and wonderful creation to a broader readership around the world.