You may recall, back in July 2019, our PI Professor Muireann Maguire went to Dublin to research Russian-Irish translator and Trinity College Dublin Russian teacher, Daisy Mackin (see blog post). Last week, RusTrans PDRA Cathy McAteer and PhD candidate Anna Maslenova returned to participate in the ‘Who’s Afraid of Translator Studies: Human Translator in Focus’ conference, 12-13 May 2022.

The exploratory aim of the conference, organised by Trinity College’s Literary & Cultural Translation PhD students, can best be summed up by the original call for papers:

‘… to explore translators’ manifestations across a variety of fields … specifically taking into account their humanity, and investigating the human touch in areas where it may not always be apparent […]. Rather than considering the technical, textual dimension to their work, this conference seeks to draw attention to the staging of the translational self, the fictional representations and literary portrayals of translators, their role throughout history and social movements, so as to rediscover translators as people with their own subjectivity and individuality.’ (my emphasis)

The call naturally piqued our interest (as researchers of historical Ru-Eng translators-cultural mediators) so out we flew to The Emerald Isle to learn what fellow scholars and PhD students are working on and to proffer our own contributions.

Day one (actually just a half day), launched with the theme of translator agency and subversive translation with lively presentations on women translators and Charlotte Lennox’s Shakespeare Illustrated (Kiawna Brewster, University of Wisconsin-Madison), the experience of Greek film translators subtitling controversial cinema during the Greek junta (Kyriaki-Evlalia Iliadou, University of Manchester), and empirical research by final-year PhD student and practising Brazilian-German translator Lucia Collischonn (University of Warwick) on exophonic L2 literary translators.

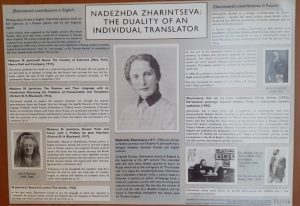

Three poster presentations interspersed the conference and Anna’s came first with her impressive A3 poster detailing the life, career and literary (especially poetic) contributions of Russian-born émigrée translator Nadezhda Zharintseva:

Thursday ended with a bang (see below) with Professor Michael Cronin’s keynote on ‘Translation, Ecology and Deep Time’, immersing us in new, complex territory where translation intersects ecological research. Professor Cronin presented concepts such as terratranslation (where ‘we mistake our world for *the* world’ and ‘posit ourselves as superior to something which we have no access – to something that we lack’ (Deer, 2021)) and nuclear translation, handling hyperobjects – a black hole, for example – and emphasised the need and urgency for Translation Studies to think translationally if we are to conceive of these phenomena.

Friday launched with ‘Human Translators in the Digital Age’, featuring ‘What does it take to be hired as an in-house translator?’ by Minna Hjort, University of Turku, and ‘Visibility of the Translator in Arabic Popular Science’ by Mohammad Aboomar, Dublin City University. Mohammad’s research is dedicated to tracing the English-Arabic translator in science journals – so far, wholly invisible (!) and the reasons yet to be discerned – and Minna, herself previously an in-house translator, is researching the hiring process for Finnish in-house translators with some shock discoveries. Experienced candidates have the potential to earn nearly 6,000 euros a month, whereas their inexperienced counterparts face a monthly salary of 2,000 euros (or less… Minna shared an advert for a Russian-English translator/interpreter offering a salary of 1350 euros/month, with expected 120 days (minimum) travel per year and work at weekends…. Imagine!).

Session three brought ‘Public (im)perceptions of translators’, starting with University of East Anglia’s Dr Motoko Akashi’s fascinating presentation, ‘Celebrity Translators: The Manifestation of their Fame in the Marketing of Foreign Fiction’ in which she revealed Haruki Murakami’s overwhelming success as a brand-forging translator and advocate of his source author, Raymond Carver, so much so that not only does Murakami’s name feature on *every* front cover, but it seems Carver is sold in Japan on account of Murakami’s involvement in the publication. A rare moment of translator eclipsing author, perhaps… but helped by publishing norms in Japan that already recognise the translator as being part of the process and readily put translators’ names on front covers.

Next came Joanna Sobesto (Jagiellonian University) presenting her microhistorical research on the various perceptions of Polish bibliographer and biographer (Tolstoy, Conrad, Dante, Mickiewicz), editor of periodicals, literary critic, translation theorist… and yes, translator too: Piotr Grzegorczyk (1894-1968) whom Joanna described as a ‘servant of greatness’ from the interwar period in Poland. And then Tereza Alfonso, commercial translator but also PhD researcher at Universidad de Salamanca on translators’ agency in the European Union, in which she presented her investigation into so-called ‘eurolect’, distinguishing between the use of official languages of the EU and working languages spoken in EU meetings and on the ground.

Time for…

(And nota bene the beautiful programme design – the pattern is a close-up of the period, hand-printed wallpaper made specially for the Georgian-era Centre for Literary and Cultural Translation (Fenian Street) when it was restored after years of being derelict.)

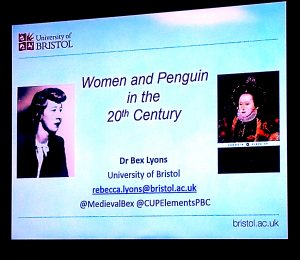

.. in which Cathy presented her latest RusTrans-funded microhistorical research on recovering forgotten or overlooked female translators of Russian literature in the twentieth century. She focused on the professional careers (the practices, networks, tribulations, and achievements), literary contributions, and socio-political contexts of quietly influential women of words – as translators and cultural mediators – during the Cold War, and connected them to their modern counterparts. (More in Tallinn next week at the History and Translation Network’s inaugural conference!)

Recovering their own translator from the archives, Dr Federica Re (Filippo Burzio Foundation, Turin) and Marco Barletta (University of Bari “Aldo Moro”) followed with an animated joint presentation on Francesco Cusani Confalonieri, translator in the Italian Risorgimento of Walter Scott and E.G. Bulwer-Lytton.

Day two’s poster presentations, ‘Translating One’s Self’ and ‘Silvia Pareschi, Negotiating America through Italian Eyes’ were given by Giulia Laddago (also of University of Bari “Aldo Moro”) and Margherita Orsi (University of Bologna) respectively:

And the very last panel offered insight into the ‘Lives, welfare and working conditions of translators’. University of Bristol PhD candidate Jincai Jiang, presented for the first time (ever) (with humour, aplomb, and excellent slides) on the lives of Chinese subtitlers on Bilibili (China’s Netflix); Bristol and Trinity Dublin alumna, Alicja Zajdel (currently University of Antwerp) explained her empirical research on the working conditions and self-perceptions of audio describers; and University of Vienna graduate researcher Daniela Schlager had the last word of the conference on an elusive, sociological question she hopes her research will answer: ‘Who is a translation expert?’

And the very last panel offered insight into the ‘Lives, welfare and working conditions of translators’. University of Bristol PhD candidate Jincai Jiang, presented for the first time (ever) (with humour, aplomb, and excellent slides) on the lives of Chinese subtitlers on Bilibili (China’s Netflix); Bristol and Trinity Dublin alumna, Alicja Zajdel (currently University of Antwerp) explained her empirical research on the working conditions and self-perceptions of audio describers; and University of Vienna graduate researcher Daniela Schlager had the last word of the conference on an elusive, sociological question she hopes her research will answer: ‘Who is a translation expert?’

‘Who’s Afraid of Translator Studies’ delivered a refreshing smorgasbord of theories and insight and exciting scope for ongoing discussion and exploration. We’re grateful to our hosts for the very warm welcome, including abundant tourist information (from the Book of Kells to Bushmills). Our thanks go to the conference organisers and panel chairs, including Andrea Bergantino, Hannah Rice, Danielle LeBlanc, John Gleeson, Nayara Guercio, and of course, to the TCLCTD team, Michael Cronin, James Hadley and Eithne Bowen.

Go raibh maith agat!

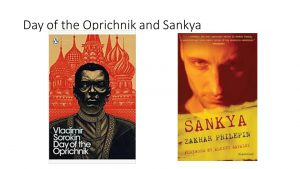

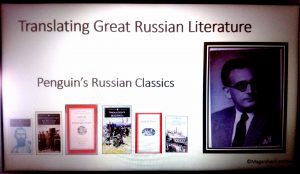

Firebird’, namely, the Western tendency to orient all Russian writers by the nineteenth century, dubbing them the latest Dostoevsky or the new Tolstoy for the benefit of readers. The curse is twofold in effect: pretentious straplines intimidate as many readers as they attract (who likens The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo to Hjalmar Soderberg? Exactly), while guaranteeing that only ‘serious’ literature gets translated. Publishers feed prior expectation that Russian literature will prove difficult, and thus it becomes the elephant on the coffee table. More perils of being a firebird: people are scared to engage with Russian authors, especially now. How do we bring a wider range of Russian authors to a wider audience? And how do you introduce any new Russian authors when key publishers have ceased Russia-related operations for the time being for obvious reasons, before other Slavonic literatures have become widely available in translation?

Firebird’, namely, the Western tendency to orient all Russian writers by the nineteenth century, dubbing them the latest Dostoevsky or the new Tolstoy for the benefit of readers. The curse is twofold in effect: pretentious straplines intimidate as many readers as they attract (who likens The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo to Hjalmar Soderberg? Exactly), while guaranteeing that only ‘serious’ literature gets translated. Publishers feed prior expectation that Russian literature will prove difficult, and thus it becomes the elephant on the coffee table. More perils of being a firebird: people are scared to engage with Russian authors, especially now. How do we bring a wider range of Russian authors to a wider audience? And how do you introduce any new Russian authors when key publishers have ceased Russia-related operations for the time being for obvious reasons, before other Slavonic literatures have become widely available in translation? The exuberant and utterly engaging Viv Groskop gave the first keynote of the conference. As an International Booker Prize juror, she confirmed our suspicions that, out of 137 titles, sadly no Russian or Ukrainian title made it to the final Booker list this year (although a Polish title did, and one (Korean) finalist studied Russian). Furthermore, in a space of seven years when 700-800 titles appeared in translation, only *three* have been by Ukrainian authors. Two of those were by Andrei Kurkov, writing in Russian. So, there’s a need to consider the role the International Booker Prize can play in deciding which books reach a world audience. Viv confirmed that cultural gatekeepers (editors, reviewers, etc.) are always operating at the level of stereotype but there is still a lot going on beneath the surface that we, as readers, can help bring out. Yes, people are worried about ‘cancel culture’, Russians are worried about the suppression of their heritage, the stats are reassuring: Kurkov sales are up 800%, while sales of Tolstoy are up too … 30%.

The exuberant and utterly engaging Viv Groskop gave the first keynote of the conference. As an International Booker Prize juror, she confirmed our suspicions that, out of 137 titles, sadly no Russian or Ukrainian title made it to the final Booker list this year (although a Polish title did, and one (Korean) finalist studied Russian). Furthermore, in a space of seven years when 700-800 titles appeared in translation, only *three* have been by Ukrainian authors. Two of those were by Andrei Kurkov, writing in Russian. So, there’s a need to consider the role the International Booker Prize can play in deciding which books reach a world audience. Viv confirmed that cultural gatekeepers (editors, reviewers, etc.) are always operating at the level of stereotype but there is still a lot going on beneath the surface that we, as readers, can help bring out. Yes, people are worried about ‘cancel culture’, Russians are worried about the suppression of their heritage, the stats are reassuring: Kurkov sales are up 800%, while sales of Tolstoy are up too … 30%. And illuminate is what Will did in Part Two of his often hilarious lecture: Все идет по плану. There are ‘1 million books published each year in the US; 500,000 self-published. 80-90% of the remaining 500,000 come out from the big 5, now the big 4. Mega-conglomerates. As a result of rapid consolidation in the ’80s there’s a lot missing’. And what’s missing takes us back to the oft-cited 3 percent. As Will summarised, ‘this includes all translations, including reprints. If you distill the 3% number down to only new translations: only about 500 out of 500,000 – that is a .1% problem. How we as readers discover books’. But Deep Vellum is a publisher of our time, publishing the US edition of Andrei Kurkov’s Grey Bees. It is now the ‘fastest-selling book in Deep Vellum’s history. Kurkov has become the voice of Ukrainian writers. He’s been here, he’s the head of PEN Ukraine, he straddles the RUSS/UKR divide. Deep Vellum publishes a lot of Russian authors, like [Alisa] Ganieva who left because they were against the war. Ulitskaya wrote against the war and her Facebook page was shut down. […] Gorbunova was arrested at a protest for holding a sign that said нет. We are living in history’.

And illuminate is what Will did in Part Two of his often hilarious lecture: Все идет по плану. There are ‘1 million books published each year in the US; 500,000 self-published. 80-90% of the remaining 500,000 come out from the big 5, now the big 4. Mega-conglomerates. As a result of rapid consolidation in the ’80s there’s a lot missing’. And what’s missing takes us back to the oft-cited 3 percent. As Will summarised, ‘this includes all translations, including reprints. If you distill the 3% number down to only new translations: only about 500 out of 500,000 – that is a .1% problem. How we as readers discover books’. But Deep Vellum is a publisher of our time, publishing the US edition of Andrei Kurkov’s Grey Bees. It is now the ‘fastest-selling book in Deep Vellum’s history. Kurkov has become the voice of Ukrainian writers. He’s been here, he’s the head of PEN Ukraine, he straddles the RUSS/UKR divide. Deep Vellum publishes a lot of Russian authors, like [Alisa] Ganieva who left because they were against the war. Ulitskaya wrote against the war and her Facebook page was shut down. […] Gorbunova was arrested at a protest for holding a sign that said нет. We are living in history’. The final word came from Peter Kaufman in his poignant keynote: Publishing Russian Literature and Culture in a World Gone Mad.

The final word came from Peter Kaufman in his poignant keynote: Publishing Russian Literature and Culture in a World Gone Mad.

Irina Kirillova

Irina Kirillova