I have purloined a Penguin title for this blog post (and no, there isn’t an apostrophe missing, it really is Penguins Progress) because it best reflects the full immersion in all things Penguin experienced at the University of Bristol’s Special Collections Penguin Archive at the end of June. Wednesday 26 June saw the inaugural gathering of researchers and enthusiasts, all sporting a variety of Penguin research backgrounds and interests, and representing a number of institutions. This was the first Penguin huddle to be held at Bristol University since the AHRC Penguin Conference in 2010 which celebrated 75 years of Penguin. Nearly a decade has passed, therefore, and we all felt it was time, once again, to share our collective knowledge about the labyrinthine ways of the archive and to discuss any new discoveries about Penguin’s place in commercial, publishing, literary, artistic, and socio-political history based on our research.

Our host from Special Collections for the day was the ever efficient and knowledgeable Hannah Lowery (seen below) the oracle when it comes to what is in the archive.

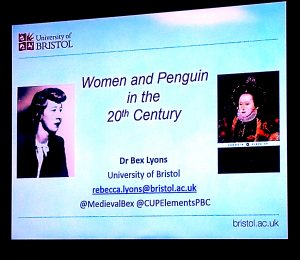

Our event organiser was University of Bristol English department’s Bex Lyons, scholar of Penguin’s medieval classics, accompanied by fellow departmental medievalist Leah Tether, classicist Robert Crowe (UoB) and art historian David Trigg (UoB). Arthurian scholar Sam Rayner joined us from UCL, where she also heads up UCL Publishing, and so too did Bath Spa’s Katharine Reeve (Publishing Subject Leader) and Laura Little (Course Director for MA Children’s Publishing). Joining me in representing the University of Exeter was Vike Plock, from the English department, and we were very fortunate indeed to be joined by James Mackay and Tim Graham, trustees from the Penguin Collector’s Society, whose knowledge of all things Penguin never ceases but to stagger!

Even Penguin researchers have to acclimatise to the climate-controlled atmosphere of Special Collections (do take extra layers if you’re thinking of going some time), but having done so, we established our common (and divergent areas) of research interest. Tackling an archive the size of Penguin’s can be difficult. It helps, therefore, to meet other researchers who might have happened upon snippets of useful information on their archival travels, files and letters which have long been filed away in an unrelated or incongruous area. For my part, for example, it’s helpful to know now – thanks to Dave Trigg – that Allen Lane popped up all over the place, wherever the topical fancy took him (not just Russia, but Europe, the Middle East, India, North and South America). On the subject of America, I now also know that Lane produced one other short-lived periodical – Transtlantic (1943-1946) – similar in concept to the Russian Review (1945-1948), but this time celebrating the US’s involvement in the Second World War and designed ‘to assist the British and American peoples to walk together in majesty and peace’ (Yates, 2006, p. 149). (Against a backdrop of paper rationing, though, this periodical was eventually sold for the nominal sum of 5 shillings, whereas the Russian Review was simply discontinued for having sold poorly from the outset. My thanks to Tim Graham for confirming the existence of this US-oriented periodical.)

We exchanged up-to-date information about permissions, archive use, online archive cataloguing (immensely useful when trying to find a needle in a haystack), and newly donated Penguin material. (Thank you, Hannah, for your overview!) We also turned our thoughts to Penguin’s next anniversary milestone, 90 years, and how we might be able to mark the occasion with a suitable celebration. (Given that my own area of research is Penguin’s Russian Classics, I can’t help but be tempted to combine – somehow – Penguin’s 90th celebration in 2025 with the 100th anniversary of Elisaveta Fen’s emigration to the UK!)

The afternoon session consisted of presentations showcasing discrete aspects of the Penguin archive. Vike Plock presented her research on Penguin’s publication in 1944 of Virginia Woolf’s The Common Reader, aptly titled given Penguin’s commitment to serve exactly that ‘the common reader’ and of particular interest to me, the only Russianist in the room, because it includes Woolf’s essay ‘The Russian Point of View’ (‘we have judged a whole literature stripped of its style’, an ideal prompt, if ever Penguin needed one, for restoring some of this stripped style in a new series of re-translations, aka Penguin’s Russian Classics).

Vike Plock introduces Penguin and Virginia Woolf

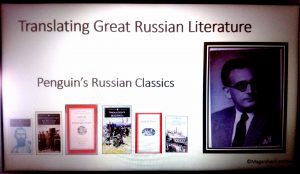

My paper was perfectly timed to follow, therefore, with a presentation on the Penguin Russian Review, Penguin’s subsequent shift to commissioning Russian Classics translations, their impact on audience reception and canon formation, and less obviously, the ongoing question for me of whether any overt link actually existed between Penguin/Lane and sympathy towards Russia and the USSR. (Articles included in the Russian Review were noticeably pro-Russia, and Russian literature was robustly represented in the Penguin Classics series, but in each case, market forces ultimately appear to trump idealism: the Review folded, and ‘non-sellers’ in the Russian titles were shelved (Lermontov’s A Hero of Our Time, for a time, and Saltykov-Shchedrin’s The Golovyov Family), regardless of their perceived standing in the Russian literary canon.)

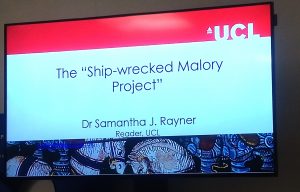

For panel two, Sam Rayner revealed the twists and turns of archival research in her pursuit of information regarding Penguin’s commissions of Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur. She described similar red herrings, dead ends and disappointments to those I have also experienced in my hunt for archival confirmation. Our mutual conclusion is: never make assumptions about commissions (they might not proceed according to plan, they can be messy and inconclusive), and never expect the last conclusive letter to be there, very often, it is not!

Penguin and Malory

Bex Lyons concluded the panel, and the workshop, with her paper on Women and Penguin in the Twentieth Century, a wonderful look at the women who played a role in Penguin’s success and who left their mark, be they Eunice ‘Frostie’ Frost (Lane’s ‘literary midwife’) or nearly forgotten wives of translators who also made their contributions, behind the scenes, to their husband’s timely submissions.

A very productive workshop. Once more, Penguins do, indeed, progress!