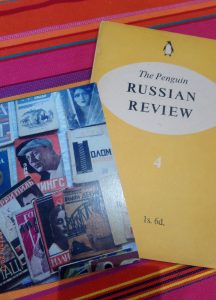

Well, it is now that I have my rare, 1948 copy of this lovely Penguin Russian Review! But more on that later.

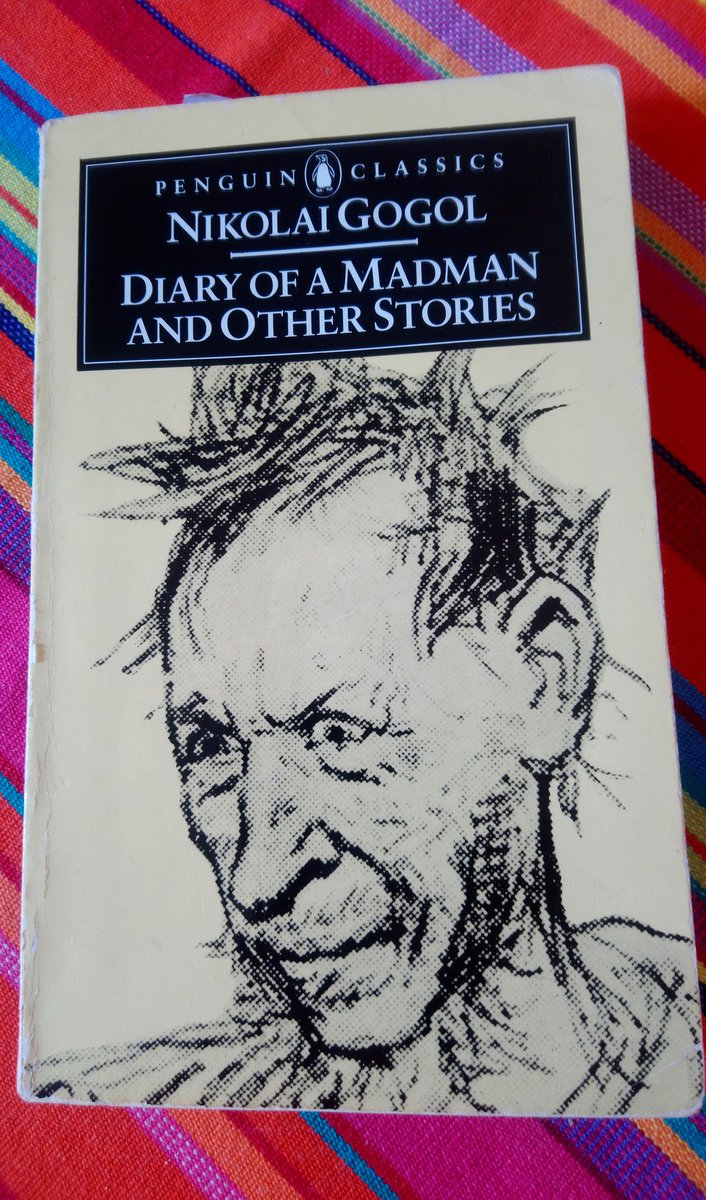

After April’s heady BASEES whirlwind (see last month’s conference blog post), May has been a month for a bit less gallivanting and a lot more researching. Whilst travel has been involved, it’s been for the sake of more solitary pursuits, i.e. archive trawling. I have been back to the Penguin archive at University of Bristol’s Special Collections, working through folders which relate to the Penguin Classics Black Cover series (post-Medallion, post-1962). And, more precisely, I have reacquainted myself with a translator whom I’d always admired, but had no idea he had been such an active Penguin translator: Ronald Wilks. This is the book – bought c. 1985, with a £3 book token – which made me realise for the first time that Ronald Wilks had arrived on the Penguin scene. (And, incidentally, it’s the book that got me hooked on Russian literature.)

What I didn’t realise was that Wilks would go on to enjoy an incredibly long tenure as one of the Penguin freelancers, far longer than the more readily known names at Penguin’s Russian Classics like David Magarshack and Rosemary Edmonds. Wilks’s first Penguin translation (Gorkii’s My Childhood) was published in 1966, and his last (Dostoevskii’s Notes from Underground and The Double) in 2009. In the interim, Wilks also translated: Gogol, Chekhov, Saltykov-Shchedrin, Tolstoi, and Pushkin. Some titles sold better than others. In a letter from 1972, Wilks expresses astonishment at how well his translation of Gorkii’s My Childhood is selling (nearly 100,000 copies sold in the space of 6 years), but this is matched by equal dismay in 1989 at the poor sales figures for his translation of Saltykov-Shchedrin’s The Golovyov Family (out of an intended print run of 6,000 copies in 1987, only 5 copies – yes, single figures, 5! – had been sold by September 1989). Ah, the high and lows of translation!

On the whole, sales figures are not easily located in the Penguin archive (there does not appear to have been any orderly system in place for recording and filing such statistics), but from these two examples, it might be possible to deduce some tentative conclusions about the reading habits of the mid- to late-twentieth-century Penguin Russian reader. Whilst the greats (Dostoevskii, Tolstoi) continued to sell as before, there is new interest in and a move towards the modern Russian classic (Gorkii). Wilks’s translations of Gorkii’s trilogy (published between 1966-1979) could be regarded as a pivotal point in the Penguin list, a gateway to the Soviet literature which would soon be commissioned for translation. Having previously doubted that Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich would amount to anything more than a ‘dead duck’ (Lane, 1963) in terms of its lasting literary merit, by 1971 Penguin was energetically pursuing publishing rights for the subsequent Solzhenitsyn novels. In addition to Gorkii and Solzhenitsyn, the 1970s saw authors like Bulgakov, Nabokov, Brodskii and Voinovich arriving on the Penguin list, but as vintage or modern classics, rather than Penguin Classics (traditionally the domain of pre-20th century works). Having trained its Anglophone readers to cope with consonant clusters, Russian names, the table of ranks, provincial regions indicated by the capital letter only (N.—), and Russian realia (samovar, verst, kopeck, smetana), Penguin introduced a new optional genre alongside its classic canonical offerings: Soviet literature.

This decisive move tempts a natural question: whether or not Penguin was (and always had been) politically motivated or – considering Cold War events like the 1968 Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, high-profile defections, Solzhenitsyn’s expulsion from the USSR in 1974 – was Penguin simply good at opportunistically tapping into what its readership would be curious to read next? After years of scouring archived correspondence, I have yet to find incontrovertible evidence of Allen Lane’s political views on Russia and the Cold War. He was certainly left-leaning and he visited Moscow in 1957, but this alone is not enough to support a notion that political motivations might be behind the Penguin Russian Classics venture. It has been necessary, therefore, to resort to the more complex process (the archival researcher’s well-trodden path) of piecing together isolated fragments of evidence (or even just hints) extracted from letters, memos, reviews, press articles which are stored in the archive (but again, there is no single folder conveniently titled ‘Allen Lane’s political preferences vis-à-vis Russia’). I’m now in the process of interpreting these hints and fragments, and fashioning them into a more informed, meaningful conclusion. One such fragment, for example, is the aforementioned Penguin Russian Review (this copy – the only one they had – was purchased at the excellent Marijana Dworski Books, and the beautiful postcard came with the book).

Not many people know or recall that Penguin published The Penguin Russian Review between 1944-1948. More often than not, people assume I’m referring to its namesake, the American Russian Review, which was founded slightly earlier in 1941. (This point is, in itself, of interest – was Penguin aware, for example, that this older journal already existed, and if so, was it hoping to gain some mileage by adopting the same name for its UK version? A question I hope to investigate during my forthcoming archive trip.) As publications go, the Russian Review series was a relatively short-lived affair, but for the purposes of this enquiry, it holds valuable insight into Penguin’s approach to Russia and the Soviet Union. Each issue (mine has 138 pages) contains contributions by Russophiles and/or Russian specialists on subjects ranging from economics, Russian literature, and geography to art, history and politics. It is perhaps particularly noteworthy that no other post-war nation qualified for a Penguin review in which to celebrate their ethnography and attempt to re-build post-war European relations.

In this particular issue (no. 4 and the last one in the series, dated January 1948, five months before the Berlin Airlift), the opening editorial commentary offers a concise summary of the near deadlocked state of post-war Anglo-Russian relations. Having painted a picture of British political intransigence towards the Russians, the anonymous editor provides a Penguin appeal for understanding: ‘People are finding it harder than they expected to make head or tail of the Russians, so hard that many have decided it is useless to go on trying. We have to go on trying all the same’ (1948, p. 7). The editor does not apportion blame for the impasse, nor is there an effort to applaud Soviet foreign policy, however the aspiration for future, bilateral harmony is clearly conveyed and Penguin volunteers itself as a vehicle for fostering just such a hope: ‘What we are trying to do is to present Russians in the round – to provide, as it were, the raw material for a practical political understanding at some future date, to remind our readers perpetually that the Russians are people with lives, traditions and outlooks of their own’ (1948, p. 8).

This same aspiration came to be shared by subsequent translators from the first cohort of Penguin’s Russian Classics, Elisaveta Fen and David Magarshack, both of whom had emigrated to the UK from post-revolutionary Russia and expressed their own concerns (independently of each other) that a bad translation could do untold damage to international perceptions of Russia and the Russians.

I will be using the rest of May to investigate more fully Penguin’s relationship with Russia through the medium of translation and ethnographic articles, and in June, I’ll be able to take my unanswered questions to a mini-conference (aka a Penguin huddle, as I like to call it) in Bristol, where Penguin specialists and scholars from all over the country will be sharing their inside knowledge of that ultimate (Emperor) Penguin – the Penguin archive. Watch this space!

Penguin archive, Special Collections, Bristol