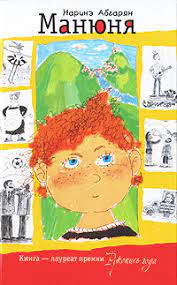

Narine Abgaryan

Excerpt from Manunia (and Me) (Манюня, 2010) by Narine Abgaryan, translated by Sîan Valvis. Read Sîan’s introduction to this extract here.

For rights enquiries, contact Natasha Banke.

Chapter 3

Everything’s fine… Nothing to see here!

“We’ll shave it off. All of it,” said Baba Rosa, doing her best impression of one of those stone statues from Easter Island.

It was hard to argue with Ba, who was about as flexible as a chunk of granite. Having discovered that Manunia and I were well and truly louse-infested, Ba had valiantly offered to keep me at her place so as not to pass on the little ‘visitors’ to my sisters.

“Oh, don’t you worry,” she had said reassuringly to my parents, who were upset after hearing the news, “I’ll soon get rid of the beggars.”

“They say kerosene’s quite effective…” said Máma timidly. “You put it on dry hair and leave it on for a bit.”

Ba gestured imperiously with her fingers, as if to zip my mother’s lips shut.

“Don’t worry, Nadia. Leave it to me.”

We slept in Manunia’s room, side by side in her bed.

“I know! Let’s get my lice to visit your lice!” said Manunia, gathering her curly, brown hair into a pony-tail and laying it above my head. “There we go,” she said happily. “Now they’re one big family.”

And so I fell asleep underneath her mass of hair. I dreamt a throng of Manunia’s lice was crossing over to my head, like Noah’s family in that painting by Ivan Aivazovsky. In the dream, Noah himself, who had the same face as Ba, was waving his staff threateningly and saying: “You naughty girl! You wouldn’t let us cross over to your sisters’ hair!”

Next morning, Ba gave us breakfast and then shooed us out into the courtyard.

“Go outside and play. I’ll do the washing up, then I’ll see to your hair,” she said.

Manunia and I trudged around the courtyard, taking it in turns to sigh mournfully. Almost ten years old—and very grown up—we certainly didn’t want to be deprived of our long hair.

“And didn’t your Pápa just give you that new hairband?” I asked Manunia. “The one with the golden ladybird?”

Manunia angrily kicked a little stone lying in the grass. It flew off and hit the tall wooden fence. “Surely she’ll leave at least a bit of hair on our heads… won’t she?” asked Manunia hopefully.

“Nope! I’m chopping off the lot!” Ba’s voice boomed behind us. “Okay, so maybe you’ll be bald for a while, but then your hair will grow back all fluffy and curly—just like Uncle Moishe’s!”

Manunia and I were horrified. We’d only ever seen faded old photos of Uncle Moishe in Ba’s family album. He was incredibly skinny, with sharp cheekbones, a prominent nose, and a magnificent bush of unruly curls.

“But we don’t want hair like Uncle Moishe’s!” we wailed in unison.

“Okay, fine,” said Ba, softening a little, “maybe not Uncle Moishe. You’ll have a mane like Janis Joplin, then!”

“Who?”

“A drug-addict and hell-raiser,” said Ba flippantly.

That shut us up.

Ba led us to the long, wooden bench underneath the old mulberry tree. She brushed away the fallen berries and motioned to me to sit down. I did as I was told. Ba stood behind me and began sheering off my long hair at the roots.

Manunia was hovering around us, oh-ing and ah-ing with every falling lock. She picked one up and held it to her head.

“Ba, what would you say if I had blond hair like this?” she asked.

“I’d say you weren’t my granddaughter,” drawled Ba, deep in thought. Then suddenly: “What a silly question,” she snapped, “what difference does it make what colour your hair is? And get that lock of hair away from your head. As if you’ve not got enough lice of your own!”

Manunia put the lock of hair on her shoulder.

“What if I were this hairy? Look Ba—I’ve got hair growing out of my shoulders!” Manunia kept chatting to distract herself, knowing with every snip of the scissors, soon it would be her turn for the chop.

“Keep on at me like this,” said Ba, “and I’ll have Nari’s ear off in a minute.”

“Don’t!” I squealed.

“Quiet, you,” said Ba. “Louse-infested. The pair of you! I just can’t, for the life of me, understand where you caught them.”

Manunia and I exchanged furtive glances. Let’s just say, we had an inkling where we might have caught them.

In the backwoods behind Manunia’s block, in an old stone house, lived Uncle Slavik, the rag-and-bone man, with his wife and all their brood. Uncle Slavik was a skinny old thing—sinewy and not much to look at. He couldn’t have weighed more than 40kg, and he looked rather like a green grasshopper with a big head. Whenever Uncle Slavik talked to you, his wide-set, unblinking eyes made you feel somewhat awkward. You’d feel your own eyes start to bulge as you struggled to maintain eye contact.

Twice a week, Uncle Slavik did the rounds, visiting all the courtyards in our little town. The wheels creaked loudly under his heavy junk cart so you could always hear when he was on his way. By the time he turned up with his three grubby little kids, all the housewives would be downstairs waiting for him. Uncle Slavik did odd jobs, like sharpening knives and scissors, and he would also buy up any unwanted household junk. Whenever he managed to actually sell something, he seemed absolutely delighted. He would then sell on any odds and ends to the gypsies who often set up camp on the outskirts of town.

Despite our parents’ strictest orders, Manunia and I used to run away to Uncle Slavik’s house and spend time with his children. We liked to play ‘school’ and pretended to be strict teachers bossing these poor little kids about. Uncle Slavik’s wife never interfered with our games; in fact, she gave us her blessing.

“They’re a law unto themselves,” she’d say, “at least you can keep them quiet.”

Telling Ba we had picked up lice from the rag-and-bone man’s children would have been the end of us. And so we kept shtum.

When Ba finished with me, Manunia gasped: “Eek! Will I look that awful, too?”

“What do you mean, awful?” Ba scooped up Manunia and pinned her deftly to the wooden bench. “You’d think all your beauty was in your hair the way you’re carrying on,” she said, shearing a long ringlet off Manunia’s crown.

I ran inside to see in the mirror—I looked horrendous! My hair had been cropped closely but unevenly, and my ears were sticking out in protest, like angry little thistles. I burst into loud sobs—never had my ears looked so hideous!

“Nari-i-i-ine!” I heard Ba’s voice from outside. “Stop admiring your ugly mug in the mirror. Come and have a look at our Manunia!”

I dragged myself out to the courtyard. From behind Ba’s mighty back, I could see Manunia’s tear-stained little face. I gulped. Manunia looked astonishing—even more ‘breath-taking’ than I did. My ears at least stuck out symmetrically, whereas Manunia’s were all over the place: one pressed neatly against her head, while the other stuck out belligerently to the side.

“There we are!” said Ba, admiring her work. “Just like Cheburashka and Crocodile Gena off the telly.

Afterwards, to the accompaniment of our loud howls, she whipped up a bowlful of shaving foam and applied it to our heads. Ten minutes later, a pair of matching billiard balls beamed brightly in the hot summer sun. Ba then marched us into the bathroom to wash away the last bits of foam.

“Whoa…” said Manunia, as we looked in the mirror. “Good thing it’s the summer holidays. Imagine being on stage with the choir looking like this!”

We burst out laughing. Now that would have been a show, all right.

“Or… or… or…” said Manunia through uncontrollable giggles, “Imagine us performing some E minor Sonata for violin and piano!!!”

We literally fell about laughing, ending up on the floor.

All we could do was shriek and howl—every time we glimpsed our closely shaved heads, we were seized by yet another fit of hysteria. Tears streaming down our cheeks, we grabbed our bellies and shook with laughter.

“Having fun?” said Ba, her voice resonating behind us. “Out you come. I’m not done with you yet!”

We rubbed our eyes and looked up. Ba was towering over us, like the Motherland Monument in Stalingrad, only instead of a sword she was holding out a bowl.

“What’s that?”

“It’s a hair-mask,” said Ba, with an air of importance, “a special hair-mask that’ll make your hair grow thick and curly.”

“What’s in it?” we asked. Picking ourselves up off the floor, we tried to stick our noses into the bowl, prompting Ba to lift it even higher out of reach.

“That’s for me to know and you to find out!” she snapped. “Listen carefully: I’ll put the mask on your heads, and then you’ll sit quietly in the sun for an hour till it’s all dry. Got it?”

“Got it!” we answered in unison. We didn’t know what Ba had in store for us, nor did we care. I can tell you now, though, we were naive. And like Ba always said, “You never know—not till you go through the change of life!” When we first heard that expression of hers, we somehow got it into our heads that ‘the change’ must have been a kind of weather condition. So every time Ba used this expression, Manunia and I looked out of the window, expecting to see some natural weather disaster.

Ba sat us down on the little bench and started applying the mask to our bald heads with a shaving brush.

“Stop fidgeting!” she shouted as Manunia tried to look at me. “Sit quietly and don’t touch or you’ll dirty your dress.”

We waited an agonising five minutes.

“There we are,” said Ba, with a look of satisfaction, “now you can go and relax.”

We gasped at the sight of each other: our heads were covered in a thick, dark blue paste. I wanted to touch it but Ba smacked my hand away.

“What did I say about touching it? Leave it alone for at least an hour!” bellowed Ba before disappearing into the house.

It was one of the rare occasions when we didn’t dare disobey Ba. Although we desperately wanted to scratch our heads, we both sat without moving a muscle. After about twenty minutes, when the mask was dry, it started to crack and crumble off. Keeping an eye out for Ba, we picked at the flaky bits, rubbing them between our fingers. They were thick, with tiny specks that instantly dyed our hands blue.

Our investigations were interrupted by the sound of the gate. We ducked behind the mulberry tree.

“Máma?” called out Uncle Misha, Manunia’s father. With a sigh of relief, we crept out from our hiding place.

Uncle Misha, who was shortsighted, stopped in his tracks. First he screwed up his eyes, then, in disbelief, he opened his eyes wider, drawing the eyelids back with his thumb, first one then the other. As we came closer, he remained transfixed, quite unable to take in the apparition before him. Seeing the look on his face, we began to whimper weakly.

“Hi Uncle Misha,” I whispered through tears.

“Well, I’ll be damned,” he said, finally regaining the ability to speak, “Girls, who did this to you?”

“It was Ba!” sobbed Manunia, so upset she could barely get her words out: “Sh-she… s-said… w-we’d… look…”

“Like Janie Jimp-Jorp!” I chimed in, also in floods of tears.

“Like who?!” said Uncle Misha, his eyes nearly popping out of his head. “Janie what-now?”

“A drug-addict and hell-raiser!” wailed Manunia and I, both now bawling uncontrollably. The full horror of what we looked like had suddenly hit us. We were bald! And we would be bald for the whole summer! No going out! No visits to the bakery to buy pastries! No swimming in the river! And worst of all—our classmates would laugh at us!

Uncle Misha backed away towards the house.

“Ma..?” he called out, “what have you done to them? I thought the deal was to put kerosene on their hair and keep them away from fire for a bit!”

Ba swept out onto the veranda.

“Shows how much you know!” she huffed. “You’ll be thanking me later when their hair’s nice and curly!”

“But… Manunia already had curly hair!”

Uncle Misha bent down to sniff our heads. “And what on earth have you smeared them with?”

“It’s a hair-mask! Fay’s recipe. You know, Fay Zhmaylik. It’s equal parts blue powdered dye and sheep droppings, then you mix it all up with egg yolk—” said Ba.

“Sheep’s what?” Manunia and I interrupted.

“Droppings! Sheep droppings!” said Uncle Misha, breaking into laughter. “In other words, sheep POO!”

Manunia and I were dumbstruck.

“Ba! How could you?” we finally wailed, legging it to the bathroom to wash the hair-mask off our heads. The poo was easy enough to wash off but our heads now had a blue tinge to them.

When we slinked back out onto the veranda, Uncle Misha let out a long whistle.

“But Máma, who said you could do this to them? Never mind Manunia—what’ll we tell Nari’s parents?”

“No need to say anything,” said Ba, cutting him off, “they’re intelligent people and unlike you, they’ll appreciate my efforts. Why don’t you call Nadia now—tell her Nari is ready to be collected.”

“I’ll do no such thing!” Uncle Misha drew us to him and gave us each a kiss on our blueish heads. “This is your mess, Ma. You clean it up.”

“Fine by me!” snorted Ba. “I’ll do it myself!”

Holding our breath, we listened tensely as Ba talked on the phone:

“Hello? Oh, hi Nadia! How are you, dear? Yes, all good, all good. You can come and pick up Nari if you like. Well… she could walk home—absolutely! Only, she’ll need a sun-hat. A SUN hat, I said! Yes, that’s right. What do you mean, ‘why’? So her scalp doesn’t burn, that’s why. Her hair? Well, with hair it’s all a matter of time, isn’t it? Hair today, gone tomorrow—that’s what I say! Haha! What are you gasping for now? Yes, well, I shaved it off, didn’t I. Kerosene? I’m not wasting good kerosene on them. Don’t worry—I’ve handled everything. I even put a hair-mask on them. One of Fay’s recipes. You know, Fay Zhmaylik? I tried to tell her: No, Fay, we don’t need any hair-masks! But would she drop it? Would she heck. Kept going on and on at me. Practically forced me, she did! So what if she’s all the way in Novorossisk? You can force people over the phone, you know! Anyway. Don’t you worry. It was just a simple homemade mask—some egg yolk, a bit of dye, and other bits and bobs. Just bits and bobs, I said. Never you mind. Well okay, sheep droppings—nothing serious. Again, with the gasping! You’d think I’d put rat poison on them… Yes, yes, everything’s fine, my dear. Only her head is a little blue. A little blue, I said. You know, like a drowned person. What are you getting upset for now? Yes, of course she’s alive! It’s just blue from the dye I mixed in. It’ll be gone in a day or two, you’ll see! And the hair will grow back in no time—it’s not like teeth, you know! Mmm, yes, okay! See you in a bit, then. Bye, dear!”

“Ma?” shouted Uncle Misha when Ba put the phone down. “Sure you didn’t hear the sound of a body dropping to the floor at the other end?”

“Darling!” said Ba, her voice full of foreboding, “Keep going like that and I’ll give you a dose of Auntie Fay’s mask, n’ all!”

Uncle Misha grunted.

“Look, you’d better give us something to eat—I’ve got to be back at work in half an hour.” He winked at us. “Now then, my little dung victims, let’s have some lunch, shall we? No sheep droppings in the food, I trust?”

Translated by Sîan Valvis. You can read more about Sîan’s translation project here.