So far, February has taken Rustrans to Bristol and London and it has brought yet more people to us: we’ve seen our network expand in all directions! If you’re not yet following us on Twitter, please do! You’ll find us here: @Rustransdark.

I (Cathy) have had two days deep in the Penguin archive at the University of Bristol researching more files on translators bright and beautiful! The list included names some of you may well recall: Ronald Wilks, Jane Kentish, Richard Freeborn, Michael Glenny, David McDuff. Fascinating and enlightening letters. Here I am, immersed, slightly dazed (book/paper spores!), but very happy:

I also took a trip to London last week, hotfooting it first of all from London St Pancras to the British Library to meet with Katya Rogachevskaia, Lead Curator East European Collections. We caught up on our latest projects and talked about any future possibilities for pooling our research, energy, and enthusiasm. Lots of exciting options (as you can tell from the photo below) which feed into our joint interests, women in translation being one of them (my research alone has six largely unsung heroines!). Thank you, Katya!

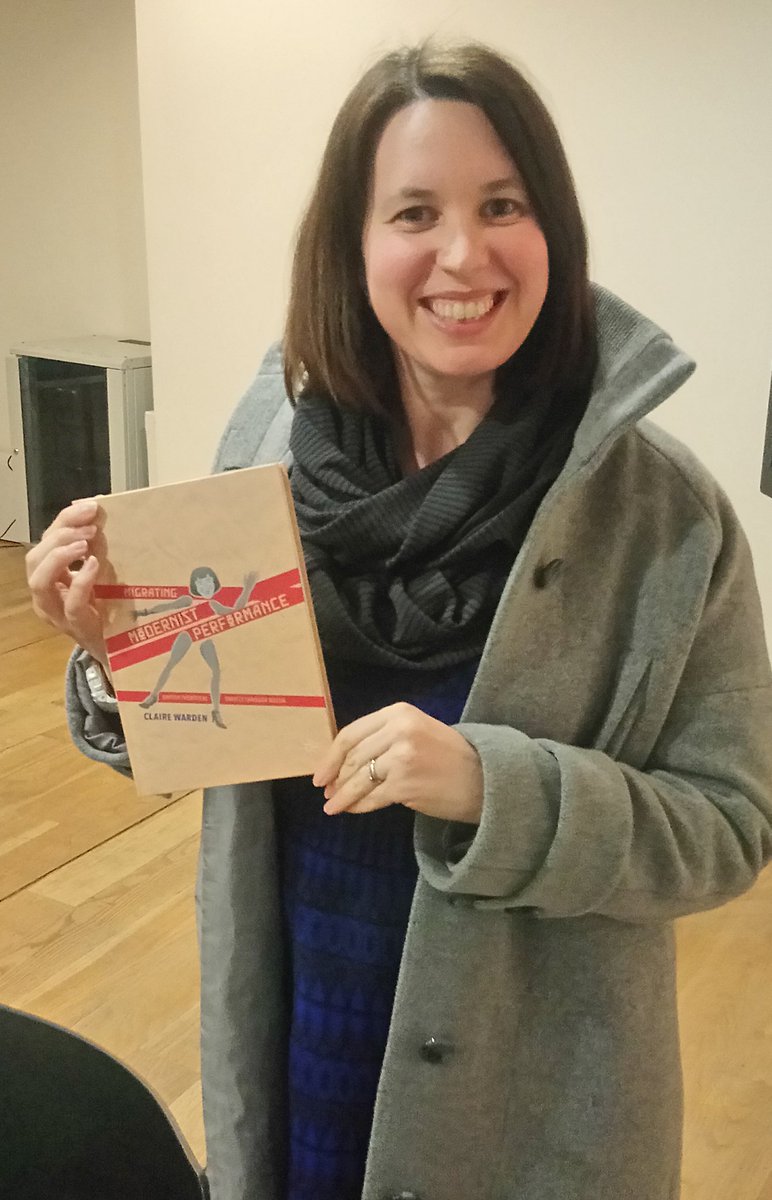

And that’s a theme which leads nicely to my next meeting in London with Becky Beasley, Matt Taunton and Claire Warden at this month’s Anglo-Russian Research Network’s reading group at Pushkin House.

Claire’s theme for the evening was ‘Re-discovering the Lost Women of Anglo-Russian Theatre’ which included, to my delight, discussion about Elisaveta Fen and her identity not just as a Russian living in the UK, but also as a translator, a medic, and an unfulfilled writer. Fen was always slightly disappointed never to have made it as a writer – her key purpose for leaving Russia, she said, was to fulfil her dream of becoming just that, a great writer – and there is a sense that translation was something of a consolation prize to her (perhaps, having studied Russian Language and Literature for her degree at Leningrad University, she associated translation with something that great Russian writers only fall back on in times of creative hardship). Certainly, she expressed surprise at being asked to translate plays into English (obviously not her mother tongue) but was encouraged to do so by an American theatre-goer, Frances Fineman, whom Fen accompanied and provided chuchotage for at stage performances in Moscow.

Fen’s Chekhov translations (commissioned by Penguin) gained a reputation among stage directors for being accessible (which is interesting for me, from a Penguin perspective, because Fen’s translations had to be rigorously edited several times, and checked by English scholars, before E.V. Rieu was satisfied with her rendering of ‘the English idiom’) and for being ‘authentically Russian’, although, as Claire was keen to point out, there is some tension here too, built into the notion of what ‘authentic’ really is, especially if it presents itself as a series of stage-bound Russian stereotypes.

Fen identified with Chekhov for two reasons. They were both products of pre-revolutionary Russia – which she ultimately preferred to the industrialised post-revolutionary Russia she encountered when she visited later – and they were both medical practitioners. Fen had a career in child psychology as well as literature; she was known as Lydia Jackson in her medical work, Elisaveta Fen for literary commissions. Our reading group concluded that, even though she failed to realise her dream of becoming a writer, she was able, through her translation work, to keep alive her nostalgia for a Russia which was changing dramatically (and, in her opinion, for the worse) under the Bolsheviks.

Aside from Fen, who took up perhaps more than her fair share of discussion time (a fact which would delight her, I’m sure), Claire also facilitated a fascinating discussion about Nikolai Evreinoff’s experimental Russian play The Theatre of the Soul, performed by the Pioneer Players in March 1915. According to the play’s translators Christopher St. John and Marie Potapenko, the play was received in March with ‘indisputable enthusiasm’. It failed, however, to get past the censor just a few months later, in October 1915, when it was scheduled to be performed at the Alhambra Theatre in honour of a fundraising event entitled ‘Russia’s Day’. (It was thought that showing a lady with a bald head might upset the usual Alhambra audience.) The play was performed instead at the subscription-based Shaftesbury Theatre, thereby circumventing the censor, but received a dismissive review in The Times, which describes it as deploying ‘a crude and easy method of characterisation’. The subtext here, according to Claire, is that being Russian and ‘avant-garde’ the play would have been regarded as scarily experimental, potentially even socially dangerous.

To the upset of archivists and archive researchers everywhere, the play’s translation drafts and correspondence were all destroyed, burnt (deliberately) in a fire. There are many unanswered questions, therefore, about how this play arrived in English. If anyone knows how it ended up here in the UK in the first place, Claire (below) will almost certainly want to hear from you. My thanks to Claire and ARRN for a fun- & fact-filled evening’s discussion!