February 2023 marks three years since we began sifting through the many submissions we received for PUBLISH, our European Research Council-funded RusTrans project to seed-fund sample translations of contemporary Russophone literature into English. To recap, we initially advertised five bursaries but we received so many exciting proposals that our project PI Professor Maguire made a case to the ERC to allow us to divide our allocated budget between a larger group. Ultimately, we were able to fund 12 translation proposals (by paying the translators for the first 10,000 words of each project at advised Society of Authors rates). These were all passion projects developed by individual translators, competitively selected from among over 30 excellent entries – our selection criteria included cultural and gender diversity, commercial appeal, and political sensitivity. Our ultimate aim with PUBLISH has been to diversify the modern Russian literary canon. All twelve of our commissions bring a unique aspect of Russian-language literature to English-language readers – all crucial reminders that while the Russian state is culpable of war crimes and political repression, individual writers are not complicit in this regime. You can read extracts from each text on our website here.

Over the last 18 months, we have asked our 12 translators to keep in touch and report on their successes and failures attempting to secure publication contracts for their RusTrans-funded projects. And, not surprisingly (in view of the many hurdles facing literary translation, the double impact of the war on Ukraine on available funding and on public attitudes to Russia), our failure rate, in the short term, has been pretty high. Some translators reached the stage of editorial review before rejection; others have not yet tempted a publisher into expressing interest. The timing was unfortunate: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine stopped the Russian-English literary translation industry in its tracks, ceasing the previous trickle of commissions with almost immediate effect. Not without some justification – since Russian literature has enjoyed near-hegemonic status among writing from the regions of the former Soviet Union, 2022 has been a year of soul-searching for translators and de-Russification for editors and publishers. We hope publishers will re-visit these pitches in time. As we know, translation pitching and publishing can be a long game.

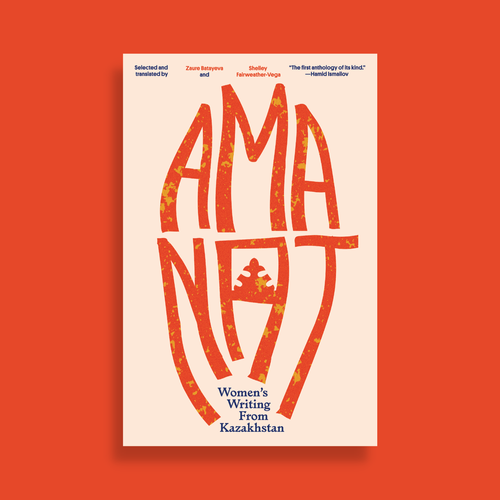

In good news, two of our twelve commissions have made it into print during 2022. We thought our first post of 2023 should be one that celebrates their success. First, Shelley Fairweather-Vega. We supported Shelley’s translation sample of Kazakh women’s writing, and Gaudy Boy Translates picked it up and published the whole collection last summer under the title Amanat. Here, Shelley tells us about what the RusTrans commission has meant to her and her women authors, how Amanat is doing six months on from publication, and about the projects she is pursuing now:

***

SFV: I’ve been more than pleased with the response to Amanat, released by Gaudy Boy Translates in July 2022. Mostly, I’ve been outright ecstatic. Coinciding with publication, the usual suspects (Voices on Central Asia, Asian Review of Books, and our friends at Words Without Borders) all published reviews or interviews to help spread the word. There were long, wonderful, surprise reviews, too, at The Millions and World Literature Today, and enthusiastic reader comments on Goodreads. But my hands-down personal favorite was the very brief mention we got at the top of Ms. Magazine’s Reads for the Rest of Us feature for July. What if Gloria Steinem herself had picked up a copy? I still blush just thinking about it. Of the half-dozen long books I’ve had published in my translation, Amanat has received the most attention by far.

The publisher reports that sales to date are oddly lower than all that buzz might have predicted, several hundred rather than the thousands I’d hoped for. Yet the collection is in libraries all over the world, and it’s being discovered by university instructors looking to teach something different in their Russian or Russophone or post-Russian literature classes. I even spoke to my mother’s book club about it, and recorded an interview that’s being distributed as a podcast through the New Books Network. I hope this means that Amanat will endure, and continue to be discovered by new readers, thinkers, and students. The collection is so diverse stylistically and thematically that I hope almost any reader will find something in it to love.

I’m continuing to work with many of the authors whose work I translated for Amanat. In January 2022, as we were editing the anthology for publication, Kazakhstan was thrown into chaos and grief by the state’s bloody suppression of political protests throughout the country. Many observers linked that month’s horrors to another historical protest that was also brutally dispersed: that of December 1986, poignantly described in Asel Omar’s story “Black Snow of December,” the translation of which was funded by RusTrans. Katherine Young and I gathered and translated some extremely moving Russophone poetry about the 2022 protests, including contributions by Asel, her fellow Amanat author Oral Arukenova, and four other, mostly younger, Kazakhstani Russophone poets, and found quick publication for the collection in the journal Suspect. In more cheerful news, the first children’s adventure book co-written by Amanat authors Zira Nauryzbai and Lilya Kalaus, Batu and the Search for the Golden Cup, will come out this June in my translation. Astute readers of Amanat will easily see Zira’s love for Kazakh mythology and Lilya’s humorous style in this new book. The work is not over, however! I’m translating two novels and an academic tome from Central Asia this year, and am always looking for ways to publish more fantastic Central Asian authors in translation.

***

Our thanks to Shelley for sharing her latest news. And our other success story lies in the realm of science-fiction (literally – the translation industry isn’t yet that desperate!). Experienced science-fiction translator Alex Shvartsman submitted a proposal to translate K.A. Teryna‘s novelette The Farctory (Farbrika), which a reviewer in The Times described as ‘a dazzling and surreal tale by Ukrainian-born K.A. Teryna, reality collapses into cardboard and cartoon once the machinery that produces colour shuts down’. Yes, Alex and Kate successfully published their story in The Best of World SF: 2 (edited by Lavie Tidhar). ‘The Farctory’ has pride of place as the anthology’s final story. In his introduction, Lavie Tidhar expresses evident pleasure at being able to reproduce this story, and even offers a rare acknowledgement of the translator’s role: ‘The translator is always overlooked, yet vital. I was lucky to have the help of Alex Shvartsman, publisher of Future SF magazine and a tireless promoter of Russian SF in translation. Alex introduced to me the fantastic work of […] K.A. Teryna, whose ‘The Farctory’ closes this book. It is published here for the first time.’

Meanwhile, Alex and Kate continue to collaborate. The next issue of Asimov’s magazine includes his translation of Kate’s story ‘The Errata’, which will be her first English-language publication of 2023. They have also put together a new proposal and are seeking an English-language publisher for Kate’s short story collection. If any publishers reading this are interested, contact Alex here or on twitter: @AShvartsman

(For those of you who want to read the Times review in full, here’s the link (it may be paywalled)).

Cathy McAteer and Muireann Maguire

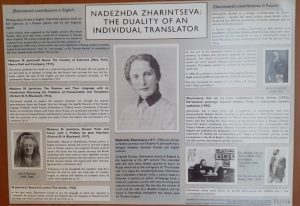

And the very last panel offered insight into the ‘Lives, welfare and working conditions of translators’. University of Bristol PhD candidate

And the very last panel offered insight into the ‘Lives, welfare and working conditions of translators’. University of Bristol PhD candidate

Firebird’, namely, the Western tendency to orient all Russian writers by the nineteenth century, dubbing them the latest Dostoevsky or the new Tolstoy for the benefit of readers. The curse is twofold in effect: pretentious straplines intimidate as many readers as they attract (who likens The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo to Hjalmar Soderberg? Exactly), while guaranteeing that only ‘serious’ literature gets translated. Publishers feed prior expectation that Russian literature will prove difficult, and thus it becomes the elephant on the coffee table. More perils of being a firebird: people are scared to engage with Russian authors, especially now. How do we bring a wider range of Russian authors to a wider audience? And how do you introduce any new Russian authors when key publishers have ceased Russia-related operations for the time being for obvious reasons, before other Slavonic literatures have become widely available in translation?

Firebird’, namely, the Western tendency to orient all Russian writers by the nineteenth century, dubbing them the latest Dostoevsky or the new Tolstoy for the benefit of readers. The curse is twofold in effect: pretentious straplines intimidate as many readers as they attract (who likens The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo to Hjalmar Soderberg? Exactly), while guaranteeing that only ‘serious’ literature gets translated. Publishers feed prior expectation that Russian literature will prove difficult, and thus it becomes the elephant on the coffee table. More perils of being a firebird: people are scared to engage with Russian authors, especially now. How do we bring a wider range of Russian authors to a wider audience? And how do you introduce any new Russian authors when key publishers have ceased Russia-related operations for the time being for obvious reasons, before other Slavonic literatures have become widely available in translation? The exuberant and utterly engaging Viv Groskop gave the first keynote of the conference. As an International Booker Prize juror, she confirmed our suspicions that, out of 137 titles, sadly no Russian or Ukrainian title made it to the final Booker list this year (although a Polish title did, and one (Korean) finalist studied Russian). Furthermore, in a space of seven years when 700-800 titles appeared in translation, only *three* have been by Ukrainian authors. Two of those were by Andrei Kurkov, writing in Russian. So, there’s a need to consider the role the International Booker Prize can play in deciding which books reach a world audience. Viv confirmed that cultural gatekeepers (editors, reviewers, etc.) are always operating at the level of stereotype but there is still a lot going on beneath the surface that we, as readers, can help bring out. Yes, people are worried about ‘cancel culture’, Russians are worried about the suppression of their heritage, the stats are reassuring: Kurkov sales are up 800%, while sales of Tolstoy are up too … 30%.

The exuberant and utterly engaging Viv Groskop gave the first keynote of the conference. As an International Booker Prize juror, she confirmed our suspicions that, out of 137 titles, sadly no Russian or Ukrainian title made it to the final Booker list this year (although a Polish title did, and one (Korean) finalist studied Russian). Furthermore, in a space of seven years when 700-800 titles appeared in translation, only *three* have been by Ukrainian authors. Two of those were by Andrei Kurkov, writing in Russian. So, there’s a need to consider the role the International Booker Prize can play in deciding which books reach a world audience. Viv confirmed that cultural gatekeepers (editors, reviewers, etc.) are always operating at the level of stereotype but there is still a lot going on beneath the surface that we, as readers, can help bring out. Yes, people are worried about ‘cancel culture’, Russians are worried about the suppression of their heritage, the stats are reassuring: Kurkov sales are up 800%, while sales of Tolstoy are up too … 30%. And illuminate is what Will did in Part Two of his often hilarious lecture: Все идет по плану. There are ‘1 million books published each year in the US; 500,000 self-published. 80-90% of the remaining 500,000 come out from the big 5, now the big 4. Mega-conglomerates. As a result of rapid consolidation in the ’80s there’s a lot missing’. And what’s missing takes us back to the oft-cited 3 percent. As Will summarised, ‘this includes all translations, including reprints. If you distill the 3% number down to only new translations: only about 500 out of 500,000 – that is a .1% problem. How we as readers discover books’. But Deep Vellum is a publisher of our time, publishing the US edition of Andrei Kurkov’s Grey Bees. It is now the ‘fastest-selling book in Deep Vellum’s history. Kurkov has become the voice of Ukrainian writers. He’s been here, he’s the head of PEN Ukraine, he straddles the RUSS/UKR divide. Deep Vellum publishes a lot of Russian authors, like [Alisa] Ganieva who left because they were against the war. Ulitskaya wrote against the war and her Facebook page was shut down. […] Gorbunova was arrested at a protest for holding a sign that said нет. We are living in history’.

And illuminate is what Will did in Part Two of his often hilarious lecture: Все идет по плану. There are ‘1 million books published each year in the US; 500,000 self-published. 80-90% of the remaining 500,000 come out from the big 5, now the big 4. Mega-conglomerates. As a result of rapid consolidation in the ’80s there’s a lot missing’. And what’s missing takes us back to the oft-cited 3 percent. As Will summarised, ‘this includes all translations, including reprints. If you distill the 3% number down to only new translations: only about 500 out of 500,000 – that is a .1% problem. How we as readers discover books’. But Deep Vellum is a publisher of our time, publishing the US edition of Andrei Kurkov’s Grey Bees. It is now the ‘fastest-selling book in Deep Vellum’s history. Kurkov has become the voice of Ukrainian writers. He’s been here, he’s the head of PEN Ukraine, he straddles the RUSS/UKR divide. Deep Vellum publishes a lot of Russian authors, like [Alisa] Ganieva who left because they were against the war. Ulitskaya wrote against the war and her Facebook page was shut down. […] Gorbunova was arrested at a protest for holding a sign that said нет. We are living in history’. The final word came from Peter Kaufman in his poignant keynote: Publishing Russian Literature and Culture in a World Gone Mad.

The final word came from Peter Kaufman in his poignant keynote: Publishing Russian Literature and Culture in a World Gone Mad.

My translations of quarantine poetry from Kazakhstan were accepted in record time, by two journals in the space of a weekend. So along with the general distress of knowing the world is falling apart around us, there has been this sense of urgency, that this is a time to work faster, more seriously – at least on topics related to the plague. Is it due to the fear that the virus could wipe us all out any day now, the sense that we have to get done as much as possible before we’re inevitably debilitated by illness or, for instance, the people who keep the internet running stop showing up for work? Or is it the perverse fear that the virus could disappear, cease being an issue, that readers could lose interest in everything being written (and translated) about it? How strange it feels to take advantage of a global calamity this way, to translate straight through the crisis, about the crisis, hoping desperately to finish your work and get it out in the world before it’s no longer relevant – while all the while also wishing desperately for the opposite, for the whole mess to disappear and for life to get back to normal, so that nobody will ever need to think, write, or translate about COVID-19 ever again. As far as I remember, there are plenty of other things to write about. Aren’t there?” – Shelley Fairweather-Vega (translator from Russian and Uzbek)

My translations of quarantine poetry from Kazakhstan were accepted in record time, by two journals in the space of a weekend. So along with the general distress of knowing the world is falling apart around us, there has been this sense of urgency, that this is a time to work faster, more seriously – at least on topics related to the plague. Is it due to the fear that the virus could wipe us all out any day now, the sense that we have to get done as much as possible before we’re inevitably debilitated by illness or, for instance, the people who keep the internet running stop showing up for work? Or is it the perverse fear that the virus could disappear, cease being an issue, that readers could lose interest in everything being written (and translated) about it? How strange it feels to take advantage of a global calamity this way, to translate straight through the crisis, about the crisis, hoping desperately to finish your work and get it out in the world before it’s no longer relevant – while all the while also wishing desperately for the opposite, for the whole mess to disappear and for life to get back to normal, so that nobody will ever need to think, write, or translate about COVID-19 ever again. As far as I remember, there are plenty of other things to write about. Aren’t there?” – Shelley Fairweather-Vega (translator from Russian and Uzbek)

Happily my publisher was able to extend the deadline for this book as there was no way I could have finished by the end of July as planned. I’ll be working on it until mid-September now, when I’m due to be starting a German nonfiction book. Every day that I’ve struggled to meet my daily translation target I have wondered whether I shouldn’t have asked for a longer extension, but I wanted to avoid further delay on the German book. I lost around £2000 worth of adjunct projects including teaching on the Warwick Translates literary translation summer school, a talk about children’s literature in translation scheduled for the ITI & Friends festival, and a translation slam at London Book Fair. I also had to cancel a weekly part-time teaching commitment because I didn’t think I could cope with teaching online alongside my ongoing translation work. But part of me was relieved when the events were cancelled as it was around March that I realised how much I had over-committed this year. I was eligible for a grant via the Self-Employment Income Support Scheme, and by coincidence it was very close to the amount I had lost due to cancelled projects. This has been a testing time but in many ways it has felt like going back a few years to when I was translating challenging books in challenging circumstances with toddlers and babies and not enough sleep. At least during the lockdown I’ve mostly had better sleep, although strangely since the lockdown has partially lifted I have struggled more with anxiety and insomnia. I think the initial weeks of lockdown were such a retreat from the normal rush that I was finally able to shut off the world and recuperate after a stressful winter. Now I have just as little time to work but need to translate five pages a day compared to the three a day I was managing at the start of lockdown; unsurprisingly, anxiety about the approaching deadline is starting to creep in. But as with every project I have found that I’ve sped up as I’ve got into the book, so fingers crossed I’ll get there in time for about a week off in between the first draft and the edits.” – Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp (translator from Russian, German, and Arabic and co-founder of

Happily my publisher was able to extend the deadline for this book as there was no way I could have finished by the end of July as planned. I’ll be working on it until mid-September now, when I’m due to be starting a German nonfiction book. Every day that I’ve struggled to meet my daily translation target I have wondered whether I shouldn’t have asked for a longer extension, but I wanted to avoid further delay on the German book. I lost around £2000 worth of adjunct projects including teaching on the Warwick Translates literary translation summer school, a talk about children’s literature in translation scheduled for the ITI & Friends festival, and a translation slam at London Book Fair. I also had to cancel a weekly part-time teaching commitment because I didn’t think I could cope with teaching online alongside my ongoing translation work. But part of me was relieved when the events were cancelled as it was around March that I realised how much I had over-committed this year. I was eligible for a grant via the Self-Employment Income Support Scheme, and by coincidence it was very close to the amount I had lost due to cancelled projects. This has been a testing time but in many ways it has felt like going back a few years to when I was translating challenging books in challenging circumstances with toddlers and babies and not enough sleep. At least during the lockdown I’ve mostly had better sleep, although strangely since the lockdown has partially lifted I have struggled more with anxiety and insomnia. I think the initial weeks of lockdown were such a retreat from the normal rush that I was finally able to shut off the world and recuperate after a stressful winter. Now I have just as little time to work but need to translate five pages a day compared to the three a day I was managing at the start of lockdown; unsurprisingly, anxiety about the approaching deadline is starting to creep in. But as with every project I have found that I’ve sped up as I’ve got into the book, so fingers crossed I’ll get there in time for about a week off in between the first draft and the edits.” – Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp (translator from Russian, German, and Arabic and co-founder of

Irina Kirillova

Irina Kirillova