February 2023 marks three years since we began sifting through the many submissions we received for PUBLISH, our European Research Council-funded RusTrans project to seed-fund sample translations of contemporary Russophone literature into English. To recap, we initially advertised five bursaries but we received so many exciting proposals that our project PI Professor Maguire made a case to the ERC to allow us to divide our allocated budget between a larger group. Ultimately, we were able to fund 12 translation proposals (by paying the translators for the first 10,000 words of each project at advised Society of Authors rates). These were all passion projects developed by individual translators, competitively selected from among over 30 excellent entries – our selection criteria included cultural and gender diversity, commercial appeal, and political sensitivity. Our ultimate aim with PUBLISH has been to diversify the modern Russian literary canon. All twelve of our commissions bring a unique aspect of Russian-language literature to English-language readers – all crucial reminders that while the Russian state is culpable of war crimes and political repression, individual writers are not complicit in this regime. You can read extracts from each text on our website here.

Over the last 18 months, we have asked our 12 translators to keep in touch and report on their successes and failures attempting to secure publication contracts for their RusTrans-funded projects. And, not surprisingly (in view of the many hurdles facing literary translation, the double impact of the war on Ukraine on available funding and on public attitudes to Russia), our failure rate, in the short term, has been pretty high. Some translators reached the stage of editorial review before rejection; others have not yet tempted a publisher into expressing interest. The timing was unfortunate: Russia’s invasion of Ukraine stopped the Russian-English literary translation industry in its tracks, ceasing the previous trickle of commissions with almost immediate effect. Not without some justification – since Russian literature has enjoyed near-hegemonic status among writing from the regions of the former Soviet Union, 2022 has been a year of soul-searching for translators and de-Russification for editors and publishers. We hope publishers will re-visit these pitches in time. As we know, translation pitching and publishing can be a long game.

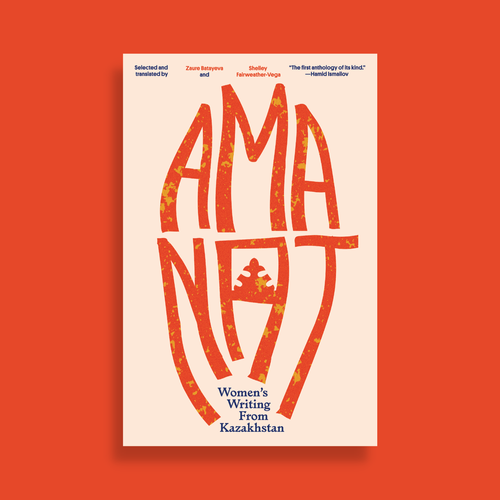

In good news, two of our twelve commissions have made it into print during 2022. We thought our first post of 2023 should be one that celebrates their success. First, Shelley Fairweather-Vega. We supported Shelley’s translation sample of Kazakh women’s writing, and Gaudy Boy Translates picked it up and published the whole collection last summer under the title Amanat. Here, Shelley tells us about what the RusTrans commission has meant to her and her women authors, how Amanat is doing six months on from publication, and about the projects she is pursuing now:

***

SFV: I’ve been more than pleased with the response to Amanat, released by Gaudy Boy Translates in July 2022. Mostly, I’ve been outright ecstatic. Coinciding with publication, the usual suspects (Voices on Central Asia, Asian Review of Books, and our friends at Words Without Borders) all published reviews or interviews to help spread the word. There were long, wonderful, surprise reviews, too, at The Millions and World Literature Today, and enthusiastic reader comments on Goodreads. But my hands-down personal favorite was the very brief mention we got at the top of Ms. Magazine’s Reads for the Rest of Us feature for July. What if Gloria Steinem herself had picked up a copy? I still blush just thinking about it. Of the half-dozen long books I’ve had published in my translation, Amanat has received the most attention by far.

The publisher reports that sales to date are oddly lower than all that buzz might have predicted, several hundred rather than the thousands I’d hoped for. Yet the collection is in libraries all over the world, and it’s being discovered by university instructors looking to teach something different in their Russian or Russophone or post-Russian literature classes. I even spoke to my mother’s book club about it, and recorded an interview that’s being distributed as a podcast through the New Books Network. I hope this means that Amanat will endure, and continue to be discovered by new readers, thinkers, and students. The collection is so diverse stylistically and thematically that I hope almost any reader will find something in it to love.

I’m continuing to work with many of the authors whose work I translated for Amanat. In January 2022, as we were editing the anthology for publication, Kazakhstan was thrown into chaos and grief by the state’s bloody suppression of political protests throughout the country. Many observers linked that month’s horrors to another historical protest that was also brutally dispersed: that of December 1986, poignantly described in Asel Omar’s story “Black Snow of December,” the translation of which was funded by RusTrans. Katherine Young and I gathered and translated some extremely moving Russophone poetry about the 2022 protests, including contributions by Asel, her fellow Amanat author Oral Arukenova, and four other, mostly younger, Kazakhstani Russophone poets, and found quick publication for the collection in the journal Suspect. In more cheerful news, the first children’s adventure book co-written by Amanat authors Zira Nauryzbai and Lilya Kalaus, Batu and the Search for the Golden Cup, will come out this June in my translation. Astute readers of Amanat will easily see Zira’s love for Kazakh mythology and Lilya’s humorous style in this new book. The work is not over, however! I’m translating two novels and an academic tome from Central Asia this year, and am always looking for ways to publish more fantastic Central Asian authors in translation.

***

Our thanks to Shelley for sharing her latest news. And our other success story lies in the realm of science-fiction (literally – the translation industry isn’t yet that desperate!). Experienced science-fiction translator Alex Shvartsman submitted a proposal to translate K.A. Teryna‘s novelette The Farctory (Farbrika), which a reviewer in The Times described as ‘a dazzling and surreal tale by Ukrainian-born K.A. Teryna, reality collapses into cardboard and cartoon once the machinery that produces colour shuts down’. Yes, Alex and Kate successfully published their story in The Best of World SF: 2 (edited by Lavie Tidhar). ‘The Farctory’ has pride of place as the anthology’s final story. In his introduction, Lavie Tidhar expresses evident pleasure at being able to reproduce this story, and even offers a rare acknowledgement of the translator’s role: ‘The translator is always overlooked, yet vital. I was lucky to have the help of Alex Shvartsman, publisher of Future SF magazine and a tireless promoter of Russian SF in translation. Alex introduced to me the fantastic work of […] K.A. Teryna, whose ‘The Farctory’ closes this book. It is published here for the first time.’

Meanwhile, Alex and Kate continue to collaborate. The next issue of Asimov’s magazine includes his translation of Kate’s story ‘The Errata’, which will be her first English-language publication of 2023. They have also put together a new proposal and are seeking an English-language publisher for Kate’s short story collection. If any publishers reading this are interested, contact Alex here or on twitter: @AShvartsman

(For those of you who want to read the Times review in full, here’s the link (it may be paywalled)).

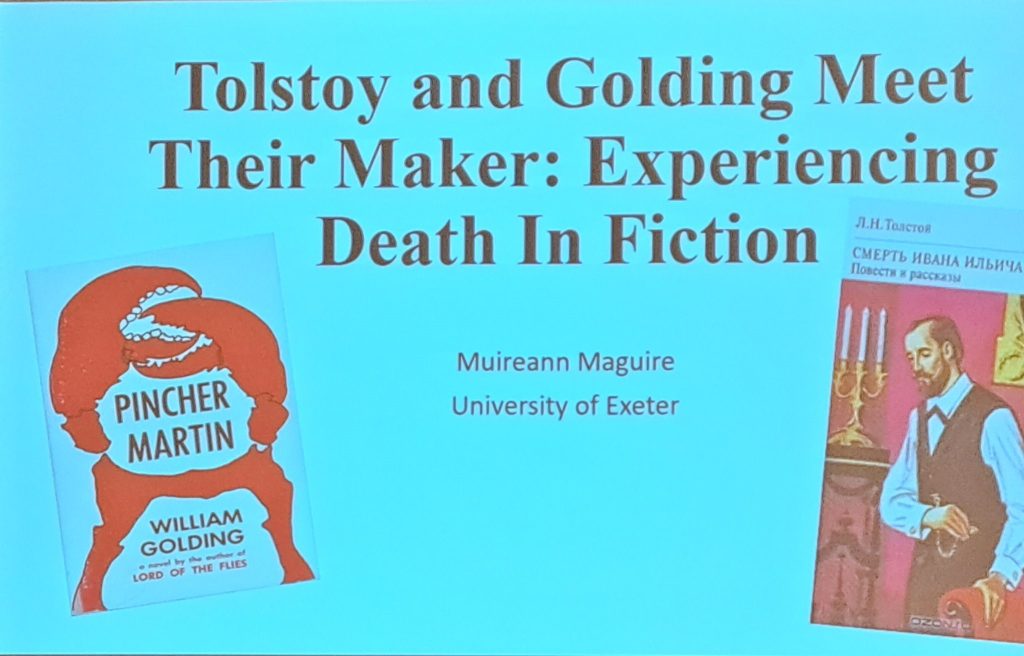

Cathy McAteer and Muireann Maguire

Isaac Sligh and Viktoria Malik (left), are currently co-translating

Isaac Sligh and Viktoria Malik (left), are currently co-translating  iPhuck 10 is part hard-boiled, Hammettesque detective thriller; part Orwellian dystopia; and part straight-up satire of the vagaries and pretensions of the contemporary art world and market. As we have said before, we believe that it is one of the major Russian novels of the 2010s awaiting translation. To potential publishers, please feel free to reach out; to readers and fans of Pelevin, please reach out as well with questions or comments. We look forward to bringing this remarkable book to you soon.

iPhuck 10 is part hard-boiled, Hammettesque detective thriller; part Orwellian dystopia; and part straight-up satire of the vagaries and pretensions of the contemporary art world and market. As we have said before, we believe that it is one of the major Russian novels of the 2010s awaiting translation. To potential publishers, please feel free to reach out; to readers and fans of Pelevin, please reach out as well with questions or comments. We look forward to bringing this remarkable book to you soon. Polly Gannon (left), the acclaimed translator of Andrei Bitov and Liudmila Ulitskaia among other major names in Russian literary fiction, is currently translating

Polly Gannon (left), the acclaimed translator of Andrei Bitov and Liudmila Ulitskaia among other major names in Russian literary fiction, is currently translating

th

th We translators are supposed to make the foreign more familiar. This is true whether we prefer to domesticate or foreignize when translating, whether we explain all aspects of the text to its new readers or leave multiple semantic and stylistic mysteries for them to consider. Even the most literal translation cannot help but make the original text more intelligible, however slightly, to readers in the new language – the mere act of using familiar words, a familiar alphabet, makes the foreign text that much more understandable, moving it from the realm of the completely incomprehensible to the realm of what could possibly be comprehended.

We translators are supposed to make the foreign more familiar. This is true whether we prefer to domesticate or foreignize when translating, whether we explain all aspects of the text to its new readers or leave multiple semantic and stylistic mysteries for them to consider. Even the most literal translation cannot help but make the original text more intelligible, however slightly, to readers in the new language – the mere act of using familiar words, a familiar alphabet, makes the foreign text that much more understandable, moving it from the realm of the completely incomprehensible to the realm of what could possibly be comprehended.

Sarah Vitali is

Sarah Vitali is