Andrei Astvatsaturov

Translator Lucy Webster is working on contemporary Russian novelist Andrei Astvatsaturov‘s autobiographical novel People In Nude [Liudi v golom, 2009] with support from a RusTrans bursary. Here she talks about the inspiration behind Astvatsaturov’s novel and why she’s passionate about pitching this novel to English-language publishers (translations into Italian and French as well as other major European languages have already appeared). You can read an extract from Lucy’s translation here.

From Peter to the Pit – The Appeal of Translating Andrei Astvatsaturov

What do my dad, a retired joiner who grew up in a British mining town in a terraced house and shared a bed with his granddad and brother, and Andrei Astvatsaturov, an associate professor at St Petersburg State University who spent his youth hanging out in shabby Leningrad loft apartments discussing philosophy, have in common? At some point during each of their lives they could be found sitting at their kitchen tables playing with figurines of sailors and Native Americans, using any old rubbish they could find to stage a battle scene.

In his first novel People in Nude Andrei Astvatsaturov draws an ironic self-portrait by recounting stories from his childhood, university years and early adult life, focusing on episodes that show how the circus of people he has encountered over the years have influenced his character. Despite the fact that, stylistically, Astvatsaturov claims to write in the American rather than the Russian tradition, seeing himself as following in the footsteps of Anderson, Hemingway, Salinger and Vonnegut rather than Dostoevsky, it cannot be denied that People in Nude is a very Russian text. His anecdotes are littered with references to classic Russian literature and Soviet realia such as poems about Lenin, the Pioneers and Little Octobrist youth organisations, and Leonid Gaidai’s classic comedies. Leningrad/St. Petersburg almost becomes a character in itself, particularly in the second part of the book, shaping the way the protagonist’s parents raised him in contrast to his fellow Jewish comrades down in Odessa and providing him with the environment required to become a member of the academic bourgeoisie so typical of the city. I’ll admit that after reading this, you might be thinking that an English-language reader could find this to be quite an alienating and unrelatable read. And yet…

What I find most appealing about Astvatsaturov’s writing, aside from his dry, deadpan sense of humour, is his uncanny ability to encourage the reader to conjure up images from their own memories, as well as envisaging Astvatsaturov’s own. Many of the earlier chapters describe interactions between Andrei and his father and feature a few memorable conversations. When translating these pieces of dialogue, I found myself thinking about how my own parents used to respond to things I said when I was younger—their quirks and set phrases—and I subsequently drew upon this to help me figure out the tone and rhythm of the characters’ reactions. Moreover, Astvatsaturov’s talent for vividly describing characters and scene setting makes it easy for any reader to relate to his experiences, regardless of whether they grew up in a different time or place to the protagonist. You don’t have to have walked around the reading rooms of the National Library of Russia in St Petersburg to be able to imagine the strange folk that often frequent a public library (trust me, I used to work in one). Everyone has encountered a surly teacher who makes you think they exist solely to antagonise you. And I’m sure there are many readers who, like my dad, spent their afternoons playing with toy soldiers and other figurines they had been bought from the local newsagents.

Of course, I’m a staunch advocate for promoting translated literature as a means of broadening our worldviews and gaining an understanding of how the world outside our Anglophone bubble works. However, I think the potential of People in Nude to highlight, broadly speaking, how surprisingly similar our experiences of certain parts of life turn out to be is just as significant as its potential to introduce readers to, say, the songs of Soviet singer and actress Taisia Kalinchenko or the writings of writer-philosopher Vasilii Rozanov. Especially at a time when the political relationship between Russian and the West is strained to say the least.

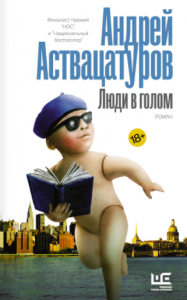

Russian cover for People In Nude

A lot of my pitch to publishers revolves around the book’s relatability and Astvatsaturov’s deceptively light and easy-going narrative voice. This makes his work a pleasure to read, particularly for those who are not necessarily in the mood to confront the classics. The most challenging part of trying to get this translation published is the fact that this is my first proper foray into literary translation, and as is the case for all emerging translators, the key is to get both Astvatsaturov’s and my name out there. This is why I decided to attend the first virtual ALTA conference last autumn and use my three pitching sessions as a first experiment in trying to get publishers interested in this text. All three seemed intrigued and wanted to know more, but only time will tell as to whether anything will come of it. I also intend to continue cold pitching to a few other UK publishers in the coming months. In the meantime, I’ve already submitted a reading of the titular chapter to the fantastic Translator’s Aloud YouTube channel as a way of promoting the sample and myself as a translator (you can watch my reading here). I’ve also been lucky enough to have been accepted onto the Bristol Translates Summer School, so hopefully this will be a great networking opportunity. It goes without saying, I am very much looking forward to learning from some of the most respected translators of Russian literature working today.

Lucy Webster

Read an extract from Lucy’s translation of People In Nude here.