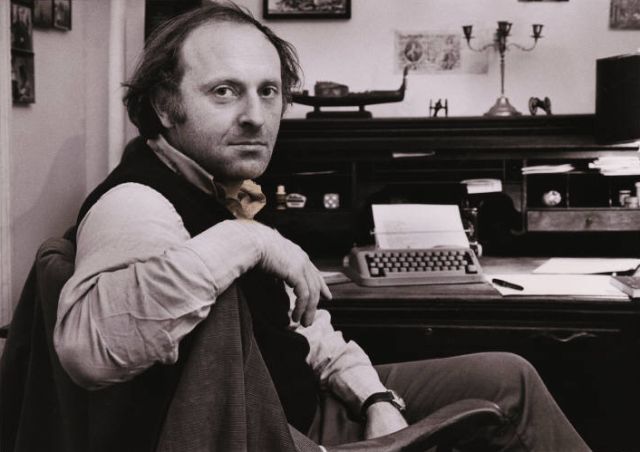

The RusTrans Team, clockwise from top left: MM, CM, CK, AM, SG

We begin our coronavirus interview series at the very beginning – with ourselves! Our team consists of five researchers, all involved in different research studies on the translation and overseas reception of Russian literature within the framework of the ERC-funded RusTrans project. As researchers, and coincidentally as female researchers, we find ourselves particularly vulnerable within one of the sectors likely to be hardest hit by the economic effects of the virus – academia. British academia in particular is threatened by a massive funding shortfall (caused by falling recruitment, particularly of high-paying overseas students), which the government is so far refusing to compensate: hiring freezes, cancellation of sabbatical leave, and a short-term shift to online teaching are just some of the immediate measures already taken or planned by university managers. Academic jobs, no longer known for their security, suddenly got a whole lot rarer – which is particularly worrying for graduate students and early career scholars. In the early stages of lockdown in the UK, it was already evident that women researchers were being disproportionately negatively affected. So, within this rather worrying context, what’s our experience – good and bad? Has our research stopped? Have we changed our plans? Read on to find out…

Dr Muireann Maguire, Principal Investigator: Parenting in Quarantine

Lockdown… where to start. Professionally, from the project perspective, there was a fusillade of disappointments straight away: the London Book Fair folded, then our first RusTrans conference, planned for April 3rd (which would have been a really exciting event with brilliant international and home speakers) had to be cancelled; various research talks I’d been invited to give were also cancelled; future conferences and talks were thrown into a state of uncertainty. Conferences are vital for academic life: we don’t just air our research and listen to other people’s ideas (although that’s clearly essential), we find real-life opportunities to talk to other people – not always a strong point for academics. We use conferences to network, which sounds rather frenetic and cliquey, but actually means making friends, discovering new connections, and mentoring younger colleagues. So it is really sad for our entire profession that these events have been paused, and that their future looks uncertain.

On the other hand, we were able to re-schedule the RusTrans conference for next year at the same venue, and lots of those same brilliant speakers have already agreed to attend; as a project team, we’d already benefited from the chance to attend several very exciting conferences in 2019, including ALTA, the translators’ Camelot; and we’re all in the happy position of having already completed such substantial amounts of archival research that we actually benefit from being forced to reflect, consolidate, and write up. I try to support my team through regular email and online conferencing. At least one of our RusTrans projects has been enhanced, rather than harmed, by lockdown: our competition to seed-fund new translations of contemporary Russian literature into English ran on schedule and has been a joy to assess – we’ve had so many exciting submissions. Moreover, I’ve been asked to be a Read Russia prize judge, which is a big responsibility and an even bigger honour.

Finding time to write is where my own problems begin. As an academic and a translator, I like to think that the psychological effect of lockdown for me is minimal. But I’m also a mother, with two young children. When schools closed, my life as a scholar broke. It broke in a good way – I’m using my skills to make my children as excited about literature and culture as I am. I’m lucky that I have a supportive partner at home who guarantees me child-free hours every day, over and above the post-bedtime oasis. Email, admin, Teams, Zoom, all those little deadlines that tick regularly round, I can handle. But to write I need the escape of a library; I need coffee shops with background chat; I need an infinity pool of silent time, a routine that’s just for me; I need to not be tired, every day. I’m the kind of person who needs to be working at 120% to feel happy with herself, and it’s an effort not to blame myself now for falling (far) short of my own expectations. I would probably have complained about all the same things before lockdown started, but now I can assure you (with every other lockdown parent out there) that the struggle is real.

Dr Cathy McAteer, Project Research Fellow: Less Confusion, More Delay

Lockdown has been a period of adjustment in so many ways (for starters, all my children plus one extra are now back home indefinitely, and I can vouch that the most frequently asked questions among 4 young adults from 9am-9pm concern food) but in terms of fulfilling my day-to-day RusTrans commitments, I’ve been lucky. I’m not campus-based, I’m a remote researcher dealing with paper more than people. I have not had to adjust, therefore, to confinement or social distancing. I do that anyway! I have, however, encountered disappointments and professional stumbling blocks. First, there have been postponements: my March 2020 Exeter-Duke fellowship at Duke University, our own RusTrans conference in April, and the annual BASEES conference for all Russian and Eurasian Studies scholars (also April), where every single member of our team was scheduled to present a paper. Next, I’ve encountered ongoing difficulties in gaining copyright permissions from a major institution for my first research monograph (due out later this year, fingers crossed). Finally, I’ve had to defer actual archival research until further notice, since all the archives are closed and the material I need isn’t necessarily digitized. Happily, there is plenty of other RusTrans work to keep me occupied in the meantime – including immersing myself in judging submissions to our translation competition – and my world feels considerably richer for accessing online reading groups such as our student Sarah’s and Pushkin House’s Facebook reading group, as well as Teams meetings, Zoom conferences (like the Center for the Humanities CUNY’s excellent Translating the Future programme), and yes, I’ll admit, the very occasional exhibition/film/live stream. Да здравствует культура!

Sarah Gear, PhD student: Successful online reading group

This has definitely been a strange couple of months, and although it has meant many cancelled opportunities, it has allowed me the time (and given me the impetus) to find new ways of reaching out to people and continuing with my research. I think the most rewarding result of this has been the online book group I started in April. Thursday evenings have now become a time to connect with readers around the world and discuss the contemporary Russian literature that I spend my days reading and researching. Our choices have been quite varied – so far we have discussed Zakhar Prilepin’s Sankya and Vladimir Sorokin’s Day of the Oprichnik, and we are just about to start Eugene Vodolazkin’s The Aviator, which will lead us down yet another avenue. Through our chats we have linked these novels to arts movements, films, podcasts, and poetry. We have contextualised the politics, and considered the themes of violence, nationalism and the impact of publishers, while discussing the novels’ translations, with invaluable contributions from both Russian and non-Russian speakers. I don’t know if the fact that everyone is participating from quarantine has added to their enthusiasm, but it is heartening to see so much genuine interest in contemporary Russian fiction, and a complete joy to discuss it with readers who have such varied perspectives. This move to online interactions has in many ways normalised the use of Zoom and Skype – and in the coming weeks and months I hope to capitalise on this, as I start to interview the translators, publishers and authors of the same books we discuss on Thursday nights. As for everyone, these past weeks haven’t been easy, but there are at least some strong positives to be found.

If you’d like to join Sarah’s reading group, please contact her here and if you’d like to fill in her reading survey, you can access it here.

Christina Karakepeli, PhD student: On missing actual books

The biggest effect the lockdown has had on my research (apart from the obvious one of not being able to go back to Greece) is that it has kept me away from books. Actual books. Not books on pdf files, books on Kindle or on online readers. I never considered the importance of studying from a book. In literature, I am and remain a staunch supporter of reading from a physical copy (despite Kindle’s amazing built-in dictionary). But when studying or researching I never had an issue with reading on my laptop. And yet, not having access these months to the library has made me rethink this relationship. A large percentage of what I need to research is available online: almost all the 19th-century Greek newspaper and periodical archives, theoretical works, literary works (thank you lax Russian copyright laws). I could jump from one book to another, have multiple tabs open, read texts in different languages simultaneously. But I kept finding myself asking for an actual book. I tried to force myself to read books, albeit online, from start to finish, trying not to get distracted by email notifications or tempted to open a new Google tab every time I saw a term or a word I did not know. There is a difference. Sitting down and dedicating time to read a theoretical work on its own maybe does not provide you with more information than what you would get from a thorough research on multiple sources, but it does allow you to delve into someone else’s train of thought and reasoning process (not to mention the treasures one can find in footnotes!); and this triggers and maybe rejuvenates your own reasoning process. In the end, it is the (sadly e-)books I’ve read in these past two months that I’ve kept turning to whenever I want to interpret new information and ask ‘what would x author think?’ before trying to form an opinion on my own.

Anna Maslenova, PhD student: No libraries, but some tea parties

It has never been easy for me to work from home, and therefore the quarantine has had a dramatic effect: it’s hard both to start and to finish working. I am trying – not always successfully – to follow a schedule on weekdays. At the beginning, my daily routine was complicated by trying to stay in touch with my family and friends at home in Russia, who were also going into lockdown; everyone was worried, so we talked by phone several times a day. But now everybody has seemingly calmed down, and life continues in ‘quarantine’ mode. I still Skype my family more often than before, since we feel the distance very keenly at the moment: it is very frustrating I cannot go back to Russia to celebrate my grandmother’s and father’s big birthdays in June as planned, but hopefully we will have a huge party when it is all over. I miss working in the British Library (the reason I moved to London), but some talks and workshops continue online. Now is a golden moment for reading, which is my main activity. Quarantine means I can finally turn to those thick volumes which I have been postponing reading for years.

Since shortly before lockdown, I’ve been lodging in London, in the attic flat of the house of an elderly Woolf scholar. She has weak lungs, and, therefore, her GP strongly recommended her to self-isolate. Thus I am very happy to help my landlady with her weekly shopping. Since I keep my distance from others during my daily constitutional, and wear a facemask and gloves while shopping, she and I decided that it would be safe enough to have a cup of tea in her garden once in a while, so I am enjoying English tea parties and some face-to-face communication sometimes.

You can read more about our team and their research here and here. Stay tuned for out next post – an interview with Russian novelist and editor Inga Kuznetsova and her Russian publisher Igor Voevodin of AST, whom we asked about the immediate effects of coronavirus on their projects and careers.

Members of the RusTrans team in simpler times