In the very last interview of our blog mini-series, RusTrans speaks to Will Evans, an award-winning publisher, writer, translator, bookstore owner, and literary arts advocate. He is the founder and executive director of Deep Vellum, a nonprofit literary arts centre and publishing house founded in 2013. He founded Deep Vellum Books in 2015, an independent bookstore in Dallas’s historic Deep Ellum neighborhood. Evans graduated from Emory University with degrees in History and Russian Literature, and received a Master’s degree in Russian Culture from Duke University. In October 2019, he was awarded CLMP’s Golden Colophon Award for Paradigm Independent Literary Publishing. Throughout the pandemic, Deep Vellum has used its Emergency Funding to support Texas writers in need (43 at the last count); it regularly donates a large proportion of website sales to charities such as LGBTQ support organizations; and recently, the publishing house was approved for a $50,000 award from the US National Endowment for the Arts that will enable it to continue reliably funding translators, authors, designers, and in-house staff.

In the very last interview of our blog mini-series, RusTrans speaks to Will Evans, an award-winning publisher, writer, translator, bookstore owner, and literary arts advocate. He is the founder and executive director of Deep Vellum, a nonprofit literary arts centre and publishing house founded in 2013. He founded Deep Vellum Books in 2015, an independent bookstore in Dallas’s historic Deep Ellum neighborhood. Evans graduated from Emory University with degrees in History and Russian Literature, and received a Master’s degree in Russian Culture from Duke University. In October 2019, he was awarded CLMP’s Golden Colophon Award for Paradigm Independent Literary Publishing. Throughout the pandemic, Deep Vellum has used its Emergency Funding to support Texas writers in need (43 at the last count); it regularly donates a large proportion of website sales to charities such as LGBTQ support organizations; and recently, the publishing house was approved for a $50,000 award from the US National Endowment for the Arts that will enable it to continue reliably funding translators, authors, designers, and in-house staff.

Quarantine, and fear for ourselves and our loved ones, have radically re-shaped how we think and behave. How have you adapted to your new working conditions? How has the crisis affected your future plans and/or your creative process?

WE: In the midst of the hardships and changes brought about by this crisis, being able to spend so much more time around my now 4-year-old son and nearly 2-year-old daughter has been a true joy. Watching them grow, reading with them, spending an incredible amount of close time together: this is something I hope I never lose after this current crisis has passed. But this crisis also calls thrown into sharp relief the value of times of physical connection (as opposed to physical office space), times when you can be in the same room with others. It exposes the need that we all have to connect in ways that are personal, professional, and profound. And I hope some day that my stress levels drop a bit so I can find more time to read on my own, to write, to translate, but that’ll be when the kids are older and we’re on to the next major global crisis of some sort. I have a couple of open translation manuscripts and novel sketches on my computer at all time, they glower at me, beg me to revisit them, and I optimistically—or naively!—think I’ll get to them all someday…

Now that’s a familiar feeling! What do you think will be the knock-on effect from lockdown on translation publishing? Are there advantages as well as disadvantages for people in the creative industry?

Now that’s a familiar feeling! What do you think will be the knock-on effect from lockdown on translation publishing? Are there advantages as well as disadvantages for people in the creative industry?

WE: I hope that all the translation publishers large and small are able to see the crisis through, and that somehow from this a new wave of publishers will emerge with fresh energy, new perspectives, and new approaches to the challenges of the industry. We always need new leaders, and our industry (publishing and the literary arts broadly interpreted), is primed for new leadership. For translation publishers, I think the greatest advantage has been witnessing the reading public’s willingness to participate in digital events. This could be transformative in how we are able to engage our authors and translators from far-flung locales in events, partnering with bookstores and organizations around the world to present these incredible books to readers anywhere and everywhere. The Internet was supposed to have already fulfilled this transformative connective potential, and yet the current crisis has, for the first time that I’ve seen in publishing, truly brought people together.

What has been the impact on your work/industry of cancelled book fairs, book launches, speaker events and so on? Is there a danger that the English-speaking world will forget Russian culture?

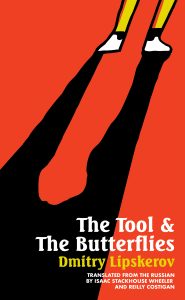

WE: The world will never forget Russian culture. Any cancelled events have led to the creation of new events, and new ways to connect, and that is inspiring. We at Deep Vellum have recently signed a few new Russian books that are going to be coming out over the next several years—two from Ludmilla Petrushevskaya, including her amazing The New Adventures of Helen & Other Magical Tales, a more positive, for her, version of the scary fairy tales we all fell in love with, translated by Jane Bugaeva, as well as Petrushevskaya’s novel Kidnapped: A Crime Story, translated by the inimitable Marian Schwartz, a book I cannot wait to see in English! We’re also preparing the English debut works of Nataliya Meshchaninova, an emerging superstar director and screenwriter in the world of Russian film and TV, whose heart-wrenching, profoundly beautiful autobiographical novel is beautifully translated by Fiona Bell, and the debut of Dmitry Lipskerov, whose hilarious satirical novel The Tool & The Butterflies is a modern-day interpretation of Gogol’s The Nose, but set in Putin’s Russia, with the narrator waking one morning missing his… tool.  It’s great. And we’re finalizing details to publish our third book by Alisa Ganieva, a writer and person I admire to the absolute highest, with her most socially engaged, political novel yet (which is saying something!), Offended Sensibilities. How can readers forget about Russian literature when this much good stuff is coming out? And between what little we at Deep Vellum are doing, we look around and eternally admire the great Russian books coming from Columbia University Press, Pushkin Press, Oneworld, and New York Review Books and just smile at the rich diversity of Russian writers whom the independent publishing world is providing for readers. But, of course, that means we all have more to do to find the broad readership each author deserves for posterity.

It’s great. And we’re finalizing details to publish our third book by Alisa Ganieva, a writer and person I admire to the absolute highest, with her most socially engaged, political novel yet (which is saying something!), Offended Sensibilities. How can readers forget about Russian literature when this much good stuff is coming out? And between what little we at Deep Vellum are doing, we look around and eternally admire the great Russian books coming from Columbia University Press, Pushkin Press, Oneworld, and New York Review Books and just smile at the rich diversity of Russian writers whom the independent publishing world is providing for readers. But, of course, that means we all have more to do to find the broad readership each author deserves for posterity.

As a publisher and bookshop owner, are you aware of increased sales thanks to locked-down populations turning to books for relief? Could this be a golden moment for reading?

WE: Some aspects of Deep Vellum’s sales are up. More and more readers buying directly from our website, which is incredibly helpful in navigating the crisis. On the other hand, our sales to bookstores have dropped precipitously and don’t look like they’ll recover any time soon. We’ll have to find a way to continue to help bookstores around the country, and the world, keep going, we need them, and we will keep putting out books that readers never knew they needed so profoundly. And every moment is a golden moment for reading if you’re reading the right things.

And finally, if you follow Russian fiction translated into English, which book(s) do you think stand a good chance of winning prizes for translated fiction – such as the Read Russia Prize (2020)?

WE: I’d be surprised if Lisa Hayden’s translation of Guzel Yakhina’s Zuleikha isn’t nominated, but I’d be shocked if Marian Schwartz’s monumental translation of Solzhenitsyn’s March 1917 cycle doesn’t win! And here’s to putting in print that whenever Robert Chandler completes his translation of Platonov’s Chevengur, that is the Russian translation (that I’m not publishing!) to which I’m most looking forward!!

WE: I’d be surprised if Lisa Hayden’s translation of Guzel Yakhina’s Zuleikha isn’t nominated, but I’d be shocked if Marian Schwartz’s monumental translation of Solzhenitsyn’s March 1917 cycle doesn’t win! And here’s to putting in print that whenever Robert Chandler completes his translation of Platonov’s Chevengur, that is the Russian translation (that I’m not publishing!) to which I’m most looking forward!!

Thank you for speaking with us, Will. Good luck with your wonderful press and thank you for sharing your enthusiasm for Russian literature! Thank you also to all our readers and followers for following this blog – we hope you’ve enjoyed it. If you have views of your own about the coronavirus crisis and its effects on the translation industry, get in touch!

I have mixed feelings about the potential effects on remote work. On a personal level, I have loved spending more time with family these past months. And I have never subscribed to the antiquated idea that publishing must happen in New York—how could anyone, with presses like

I have mixed feelings about the potential effects on remote work. On a personal level, I have loved spending more time with family these past months. And I have never subscribed to the antiquated idea that publishing must happen in New York—how could anyone, with presses like

fact that they so easily result in recordings means that their marketing potential lives on well after the event (see, for example,

fact that they so easily result in recordings means that their marketing potential lives on well after the event (see, for example,  And finally, if you follow Russian fiction translated into English, which book(s) do you think stand a good chance of winning prizes for translated fiction – such as the Read Russia Prize (2020)?

And finally, if you follow Russian fiction translated into English, which book(s) do you think stand a good chance of winning prizes for translated fiction – such as the Read Russia Prize (2020)?

No matter how well established a translator might seem to be, the freelance life is only as viable as the next contract, and up until a month ago, as I turned in the fourth and final volume of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s documentary novel

No matter how well established a translator might seem to be, the freelance life is only as viable as the next contract, and up until a month ago, as I turned in the fourth and final volume of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s documentary novel  There is no danger that the English-speaking world will forget Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, or Chekhov, but there is a tremendous danger that they will never have a chance to read, let alone forget, much of post-Soviet and especially twenty-first century Russian literature, given that interest in contemporary Russian writing already seemed at an all-time low, despite the work of several excellent independent presses and new efforts such as the

There is no danger that the English-speaking world will forget Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, or Chekhov, but there is a tremendous danger that they will never have a chance to read, let alone forget, much of post-Soviet and especially twenty-first century Russian literature, given that interest in contemporary Russian writing already seemed at an all-time low, despite the work of several excellent independent presses and new efforts such as the  This week RusTrans spoke to Peter B. Kaufman, President and Executive Director of

This week RusTrans spoke to Peter B. Kaufman, President and Executive Director of  What do you think will be the knock-on effect from lockdown on translation publishing? Are there advantages as well as disadvantages for people in the creative industry?

What do you think will be the knock-on effect from lockdown on translation publishing? Are there advantages as well as disadvantages for people in the creative industry?

The Russian

The Russian

optimistic, but this seems impossible to me.

optimistic, but this seems impossible to me. In today’s post we speak to Clem Cecil, outgoing Executive Director of

In today’s post we speak to Clem Cecil, outgoing Executive Director of  Clem Cecil has been Director of Pushkin House since April 2016, and from June 2020 is leaving to work on a book about Moscow. She is former Moscow correspondent for The Times, and co-founder of the Moscow Architecture Preservation Society. She has co-edited four books on the threatened architecture of Moscow, Samara and St Petersburg. From 2012 to 2016 she was the Director of SAVE Britain’s Heritage and SAVE Europe’s Heritage.

Clem Cecil has been Director of Pushkin House since April 2016, and from June 2020 is leaving to work on a book about Moscow. She is former Moscow correspondent for The Times, and co-founder of the Moscow Architecture Preservation Society. She has co-edited four books on the threatened architecture of Moscow, Samara and St Petersburg. From 2012 to 2016 she was the Director of SAVE Britain’s Heritage and SAVE Europe’s Heritage.