American poet and Russian translator Katherine Young and I met for tea in Russell Square on Tuesday afternoon this week. I confessed during our conversation that, for me at least, poetry translation feels like the ultimate art form when it comes to crafting words. The pinnacle of the translation world. To hear Katherine present her poetry translations at Pushkin House later that evening – my thoughts were proved right. This week, Rustrans came to London for Manuscripts Burn, an evening listening to Katherine recite and talk about her translations of politically charged war poetry and literature.

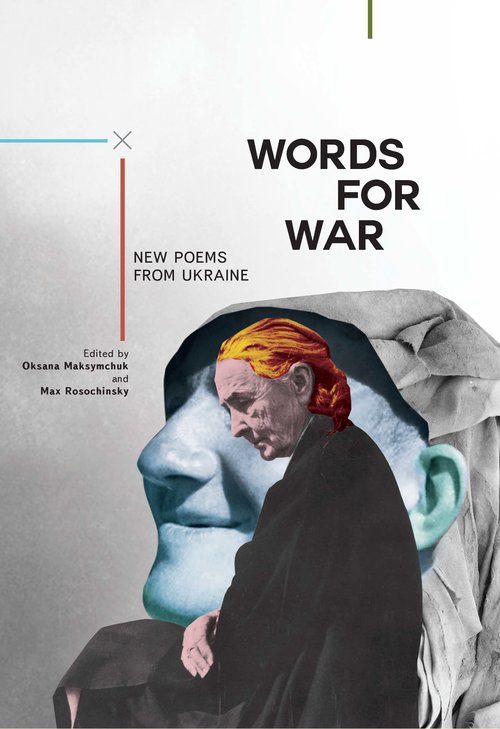

Katherine split the evening in two parts: poetry and prose, with case studies concerning the literary usage of Russian as a source language in Ukraine and Azerbaijan. Katherine first provided detailed background information to poets affected by the Russia-Ukraine conflict: Lyudmila Khersonska, Inna Kabysh, Xenia Emelyanova, and Iya Kiva. All the poems feature in the Words for War anthology (see below), edited by a Russian-Ukrainian couple now living in the US, Oksana Maksymchuk and Max Rosochinsky, who wanted to document the collective experience of war, especially the impact of war on people away from the field of battle.

The poems which followed were acts of civic witness and demonstrated a moral clarity which, as Katherine pointed out, touches on politics. Lyudmila Khersonska, writing in Russian, lives in Odessa and has four collections of poetry. Her trademark style is one of beautiful, powerful but often tragic images created through meteorological and botanical references, a poetic-pathetic fallacy of thunder, lightning, snow, hurricane, hail. Nature responding to war with elemental force. When faced with poems rooted in culture- and event-specific references (little green men, Crimea’s annexation), Katherine identified as one of the translator’s key challenges the need to render a poem without voluminous footnotes. So, once again, I feel justified in putting poetry translation high on the wordsmithing pedestal.

Katherine introduced Inna Kabysh’s poetry, describing her style as deeply personal, anguished, movingly religious in its motifs. Her poetry tiptoes round politics and acts as testimony to the sorrow and dismay that many Russians feel about the conflict with Ukraine. Katherine recited from one of Kabysh’s long poems (Sevastopol Stories), painting a stark picture of ravaged Ukraine, one of graves, destroyed orchards, ‘If there’s no God, I’ll tell him – be’.

Xenia Emelyanova grew up in post-USSR. Her poetic discourse is described as ‘highly self-conscious and sceptical’ and she is tipped as one of the next big things in Russian poetry. Just after the Russia-Ukraine conflict broke out in 2014, Emelyanova wrote a poem, recited it on camera, and released it on social media, not knowing how it would be received. With lines like ‘It’s time to shake off our impotence, Stop the slaughter, stop the war’, it’s easy to understand the trepidation over what responses her verse might prompt. Katherine consulted fellow poets to debate the moral quandary of whether to translate Emelyanova’s work, the concern being that Emelyanova might be exposed to danger. The consensus among poet-translators, though, was that poets write to have their voices heard, and so Katherine translated it. Poet-translators have since faced further moral dilemmas: whether to ‘like’ activist poetry on Facebook or not, for fear of upsetting personal and professional diplomatic relations (maybe even putting future visas at risk); and whether to accept invitations to judge a poetry prize in occupied Ukraine which, inevitably, would provoke moral and ethical judgments from expectant onlookers. At the same time, Katherine explained that US publishers tend not to know what is going on in places like Ukraine, so translator-activists face home-grown difficulties of their own when trying to get political poetry published in English.

My personal favourite was a poem by Russian-speaking, Jewish poet Iya Kiva, who used to live in Donetsk before the 2014 outbreak of war. Her father was killed while fighting in the conflict and she now lives as a refugee in Kiev. Her poetry mirrors the hand-to-mouth existence she now lives there; words and images pared down to absolute simplicity, the only appropriate way to express herself after all she has experienced. The poem I loved has no title, but starts:

is there hot war in the tap,

is there cold war in the tap,

how is it that there’s absolutely no war

it was promised for after lunch

we saw the announcement with our own eyes

‘war will arrive at fourteen hundred hours’

You can read the rest of Katherine’s translation here: https://www.asymptotejournal.com/poetry/iya-kiva-a-little-further-from-heaven/ and Katherine’s poems – each one greeted with reverence and artistic appreciation – can be found in Words for War: https://www.academicstudiespress.com/ukrainianstudies/wordsforwar

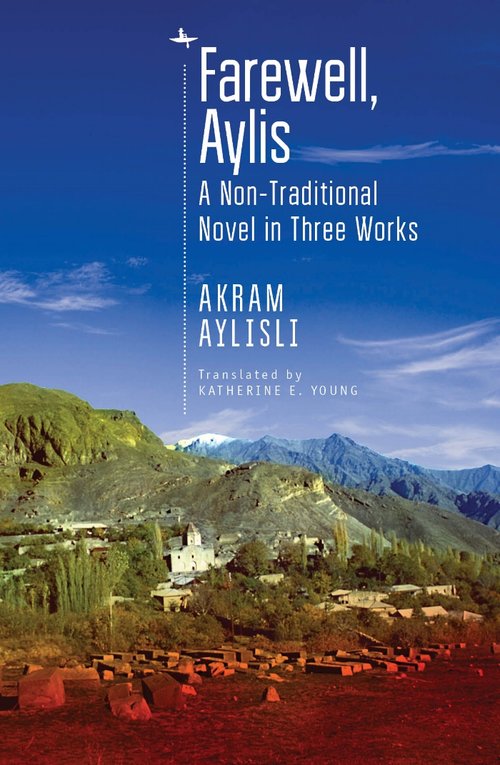

Katherine then moved to her second case study, that of the prominent Azeri-born, Russian writing novelist Akram Aylisli (born in 1937), who is now a de facto political prisoner and held effectively under house arrest. Aylisli’s act of civic witness transcends two generations, his own and his mother’s. His mother witnessed part of the Armenian genocide and, as the village storyteller, she voiced an account of the events she had seen (‘They drowned Armenians in their own blood’). Much later, Aylisli wrote an account of Azeri history, spanning his story of socio-political upheaval, ethnic cleansing, and corruption over three novellas under the overarching title Farewell, Aylis. The first novella was published without problem, but the remaining two are more graphic. Originally, Aylisli had no intention of publishing these two stories, but in 2004, a single event changed his mind. At the NATO Partnership for Peace Training Programme in Budapest, an Armenian army officer was hacked to death in his bed by his axe-wielding Azeri counterpart. Aylisli was moved to print his remaining novellas after the Azeri officer was given a hero’s welcome on returning home. Azeri outrage at Aylisli’s novellas manifested in a variety of ways: his books were burned in Baku in 2013 (manuscripts do burn, after all, Bulgakov); Aylisli’s wife and son were fired from their jobs; an empty coffin was paraded outside their house; and a reward was offered for cutting off Aylisli’s ear.

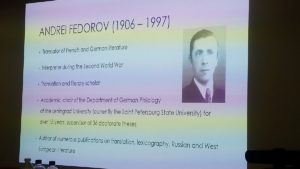

Aylisli wrote his books in Russian both during and after the Soviet Union. There is no authoritative version of his works in Azeri, but his works have been translated (one of his novellas was shortlisted for the German Booker prize) and are popular in Armenia. Aylisli relies on Russian support for his literary success and his work has been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize. On 30 March 2016 (tomorrow marks the third anniversary), Aylisli was detained at the airport while on his way to a literary festival in Italy; after resisting the authorities with violence, he had his passport confiscated, which means he has not since been able to access the medication he needs. Katherine was made aware of Aylisli by Glas editor Natasha Perova. Perova wrote to her saying, ‘I understand you like to take on lost causes; I have one for you’. At first, Katherine thought that publicity would suffice, but soon realised that Aylisli’s case required more than that. Katherine has become Aylisli’s agent and translator – in itself, an arrangement of competing interests which, Katherine recognises, must be managed ethically – she raises awareness of his situation and, of course, translates his work, of which she is very proud.

Thank you, Katherine, for a most remarkable, thought-provoking evening.

Katherine Young