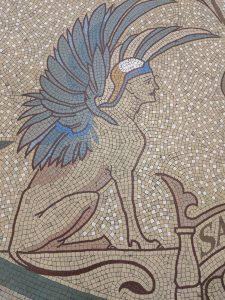

A thoughtful sphinx from the National Library of Ireland

“We must get into touch also with our contemporaries, – in France, in Russia, in Norway, in Finland, in Bohemia, in Hungary, wherever, in short, vital literature is being produced on the face of the globe,” wrote Padraig Pearse, Irish writer, schoolteacher, poet, revolutionary martyr and legend – here, campaigning against what he perceived as the parochialism of the Irish literary revival up to 1906, the time of writing. Ever since the foundation of the Gaelic League (Conradh na Gaeilge) in 1893, the movement to create a vibrant and original Irish-language literature had been gathering impetus. Over the next four decades, major Irish writers would choose Russian literary models – principally Turgenev and Gorky, but also Tolstoy and Chekhov – to inspire new literary styles that were both realist and experimental.

My first RusTrans-related research project, with the working title “Pushkin on Grafton Street” is a study of the influence of Russian realist literature, in translation, on the formation of Irish literary consciousness in the first half of the twentieth century. To this end, I am reading fiction, memoirs, and critical essays by Padraig Pearse, Daniel Corkery, Padraig Colum, Padraig O Conaire, Seamus and Seosamh O Grianna, Máirtín Ó Cadhain, and a few others, to map the reception of Russian themes and styles by these major early (and mostly Irish-language) writers. This was a very self-aware process; Máirtín Ó Cadhain in particular was very conscious of the danger of sovietizing Irish letters by over-encouraging writers to adhere to set aesthetic standards, which could prove as sterile as the excesses of Socialist Realism; as he put it, the worst new Irish writing was “as harmless as cement or tractor novels”.

A secondary research direction is translation itself: a major early achievement of the young Irish Free State (it became independent of Britain in 1922) was the foundation of An Gúm (“The Project”), which commissioned both new Irish-language fiction and translations into Irish from English and other languages. There was surprising enthusiasm for translating from Russian into Irish, as various versions of Tolstoy short stories on the pages of Irish-language newspapers attest. Not all these versions were translated from Russian, however; most appeared

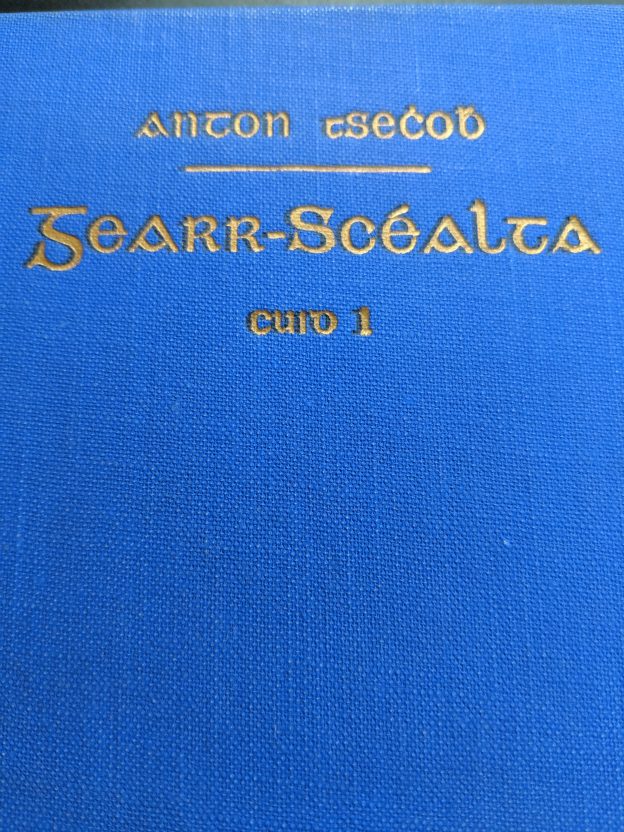

Chekhov, Short Stories (translated by Daisy Mackin, 1939)

in Irish via an English-language crib. One of the only translators to work exclusively from Russian to Irish was the uniquely experienced Maighréad Nic Mhaicín, known as Daisy Mackin, a young woman originally from Donegal, who had studied at the Sorbonne, worked as a translator in Moscow, and later taught Russian at Trinity College Dublin for three decades. An Gúm paid Daisy Mackin to translate Turgenev and Chekhov into Irish, but funding dried up after the Second World War. One of the most exciting discoveries of my research trip to Dublin was a complete handwritten, final-draft manuscript of Daisy’s Irish translation of Konstantin Simonov’s wartime play Russian People. Never performed or published, it sits in the archives of Ireland’s National Library inviting some ambitious director to take it on. I am very grateful to Daisy’s daughter Mairead Breslin Kelly for allowing me to interview her about her fascinating parents and to reproduce images like the picture of a formal visit to Moscow in the 1960s by academics from Trinity College Dublin and Queen’s University Belfast, including both Daisy (front) and Máirtín Ó Cadhain (far right), who became Professor of Irish at Trinity towards the end of his life.

Irish visitors in Pushkin Square, Moscow

Which brings me to the personal element of this post: the joy of working in one of Dublin’s most beautiful buildings, the National Library of Ireland. Every library and archive has its own rules, which take time to learn (hence the title of this blog; perhaps also, given the subject, a nod to the espionage tradition of playing by “Berlin Rules”, etc.). The library boasts marble floors, a sweeping staircase that rises in a double curve to the reading room, and an overabundance of carved griffons, lions, and other mythological creatures. It took me a while to get used to the automated system (especially to access manuscripts), but the staff were friendly and helpful. The Early Printed Books reading room in Trinity College library, where I accessed volumes of Sean O’Faolain’s Herzen-inspired journal The Bell, was another treat: you reach it via a lengthy tunnel and a narrow, concrete spiral staircase which comes out in the same building where the Book of Kells is kept. Next time I return to this research, I may well be learning Galway Rules as I follow up the archives of the O Grianna brothers in NUI Galway.

A carving from the National Library of Ireland