There is a particular scholarly lens which suggests that Russian literature is always behind developments in the West. Russian drama? Developed from French prototypes. The first Russian novel? Cribbed from various European precursors (if we believe the Countess in Pushkin’s The Queen of Spades). Major literary movements, like realism, symbolism, or futurism? All derived, with a lag of a decade or more, from French or Italian prototypes.

In the current case, however, Russian literature is far ahead of the West. Fifty years, to be precise. I have in mind the poet and translator Joseph Brodsky’s 1970 poem ‘Don’t Leave Your Room’ (‘Не выходи из комнаты’), which could have been written especially to console and beguile everyone sheltering in place or self-isolating during the current coronavirus crisis. The poem gently mocks our expectations of the outside world (‘It’s not exactly France out there’ – with apologies, no doubt, to any readers based in that country), while inciting the reader to live their best lives in the privacy of their home – which might well involve dancing the bossa nova while naked under an overcoat. Nor is it written from a place of privilege – Brodsky ironically celebrates a room within a communal apartment as a capsule of perfect privacy (albeit scented with boiled cabbage). If you need an excuse to stay home, Brodsky suggests claiming you’ve caught a chill – and he specifically names a Virus as one of the dangers of the outside world. Clearly, with this one poem, Russian literature was well ahead of the historical curve.

You can read Brodsky’s poem in the original, with a vibrant facing-page translation by Thomas de Waal, here on the site of our friends at Pushkin House.

Given this fifty-year head start, how is Russian literature responding to the personal and psychological impact of the current crisis? More specifically, how can literature as we know it survive? Starting even before the cancellation of the London Book Fair in March 2020 (where many important Russian writers and intellectuals would have been hosted at the Russian Book Stand), and extending to the mass closure of bookshops and their suppliers, the postponement of new title launches and even book prizes, and uncertainty over the format of future events such as the Frankfurt Book Fair, which is still scheduled to take place in October this year, and with only limited glimmers of hope, the industry is clearly facing into a rocky period. With translated literature always a niche market in the Anglophone West, how will the translation and dissemination of Russian literature be affected? We at RusTrans decided to find out. We spoke to leading translators, publishers, writers, and members of key cultural institutions (such as Pushkin House and the Russian Institute of Translation) to produce a composite picture of the immediate effects of the coronavirus crisis on the translation and publication of Russian literature. Follow us on this blog or on Twitter @Rustransdark for regular interviews with the people behind the scenes in Russian literature, telling us how they feel the virus will change their industry. And don’t forget – don’t leave your room.

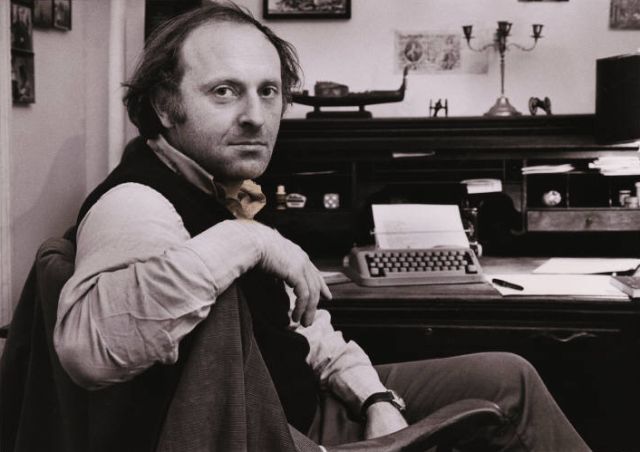

Joseph Brodsky in his room