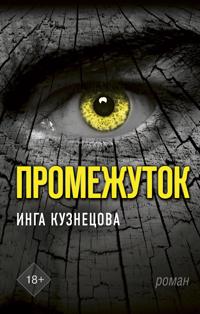

How has the current COVID_19 pandemic affected writers and publishers in Russia? To find out more, RusTrans spoke to Igor Voevodin, a senior editor at AST, one of Russia’s largest and most prestigious publishing houses, and Inga Kuznetsova, a poet and novelist whose second novel Intervals (Промежуток) was published by AST in 2019.

Quarantine, and fear for ourselves and our loved ones, have radically re-shaped how we think and behave. How have you adapted to your new working conditions? How has the crisis affected your future plans and/or your creative process?

Igor Voevodin

IGOR: I think that the pandemic and the economic crisis that follows will stimulate a new role for culture in the new millennium. The world is changing fundamentally. Editors and writers who understand this will be able to contend for a place in readers’ hearts – and on their bookshelves. We all need new great books now, because great books can inspire us for the struggle ahead. We can all contribute to creating a new world. Writers, editors, and people from all cultural areas have the chance to be present at the start of a brand-new culture. As an AST editor, I’m constantly looking for new authors, new formats for books and new literary trends. At the start of April, I published Oleg Zobern’s Chronicle of a Time of Plague (Khroniki chumnovo vremeni), a provocative experimental novel which is also the first fictional exploration of the peculiarities of Russian quarantine – an ironic version of the Decameron. Like Oleg Zobern, I’m experimenting on our readers – hoping to provoke, to startle, and even to force people to venture out of their own little worlds and to realize that mankind is not Planet Earth’s sole inhabitant of .

INGA: As, for me, working on a novel takes up whole islands in the stream of time – it’s a kind of Robinson Crusoe existence, requiring enthusiasm, courage, and self-restraint where socializing is concerned. I would say that my life for at least several months, even before the pandemic, resembled voluntary self-isolation. But the key word here is voluntary. I love people; I’m not a cat person or a dog person, I’m a people person. After long stretches of work on a book, I’m normally delighted to spend time with my friends and family, like a puppy let off the leash. Right now that’s impossible, and it’s hard for me. It’s difficult to be away from my loved ones, unable to hug them, joke with them, share goodwill with them (phone conversations and letters are just not the same thing). Even the creative writing group I ran for teenagers in my little town of Protvino near Moscow has had to close temporarily.

What do you think will be the knock-on effect from lockdown on publishing, at home as well as the overseas market for Russian fiction in translation? Are there advantages as well as disadvantages for people in the creative industry?

IGOR: I think that translations of Russian novels will take off again. But European readers will need new books and new themes that appeal to them. The current situation gives writers a chance to stop and think about where we’re all headed, about who sent us in this direction, and what responsibility they have towards themselves and their readers. I hope that the creative industry will drop fixed ideas and old ways of thinking.

What has been the impact on your personal plans or work of cancelled book fairs, book launches, speaker events and so on? Is there a danger that the English-speaking world will forget Russian culture?

Russian cover of Intervals

INGA: On March 8th (2019) we were due to fly in for the London Book Fair to launch my new book Intervals, written and published the previous year. The Book Fair was cancelled a few days in advance. March 8th was the last day that I was in Moscow and met with my friends there. Since my son and my elderly parents are both in high-risk groups (for medical reasons), I decided then to stop travelling to the big city, where I work, well in advance of the government’s self-isolation measures. All my literary colleagues, my sister and my closest friends are in Moscow, 120 kilometres away; I’ve now been cut off from them for two months. Sometimes the Russian government’s strict controls make me think the dystopia described in my novel might be coming true: my publisher jokes that we’re all now living in the world of Intervals, which I wrote in the summer of 2019, well before all this. It’s possible that the coronavirus has caused the fairly conservative jury members of one of our national prizes to turn towards dystopian novels. It’s possible that readers who were accustomed to conventional prose will now be receptive to more radical experimental styles and perspectives in their fiction. As harsh as it sounds, dystopia is coming true all around us, and the coronavirus is helping some writers get attention.

IGOR: The cancellation of public events [like the LBF] has severely affected our business plans. Overseas sales of rights to Russian novels have fallen in the first half of this year, precisely because international book fairs (where AST normally participates actively) have been cancelled. But it’s also given us time to reconsider and reexamine our publishing models, to come up with new ideas and new ways to carry them out. I don’t think there’s any need to worry that Russian culture will be forgotten. Russia will continue to be a country in which the tectonic plates of culture are always colliding, erupting literary lava. Or to put it another way, this is a country where the tension between state and individuals, society’s values and personal beliefs will go on striking sparks. Russian writers have much to say to European readers. And what they say is so fierce and so genuine, it always stimulates deeper thought.

Are you aware of increased sales thanks to locked-down populations turning to books for relief? Could this be a golden moment for reading?

IGOR: As an editor and a publisher employed in Russia’s biggest publishing firm, I am aware that book sales in this country fell by 60% during April. This fall is predicted to continue. This is caused, in the first place, by the closure of all physical shops and publishing firms due to quarantine, and also the closure of several online bookshops. AST, however, has released a series of e-books and audiobooks called “Stay Home and Read”; the series includes new titles by some of our best authors. Although “Stay Home and Read” has been popular with readers and commercially successful, it can’t compensate for the lack of sales of print books, which provide our basic income.

Quarantine is a golden moment not just for readers, but for writers, who should re-think whether their ideas are needed in our changed world. We can say that this is a critical moment for literature: the start of a new millennium. Old themes and genres will disappear into the void together with their authors: only writers who can offer their readers a new sincerity will survive.

Inga Kuznetsova

INGA: Since February, I’ve constantly monitored news about the coronavirus, yet I couldn’t really understand it: all the information was either contradictory or not objective enough. I even had panic attacks. I only began coping with my anxiety after I found a speaker who finally made sense: a Russian-American geneticist, Ancha Baranova. I knew straightaway that I had to write a book with her. I convinced my publisher, AST, to let me edit a book based on interviews with Ancha – a book which I managed to complete in just 5 days. The whole editorial teams worked long hours for very little pay, motivated (and this is no exaggeration) by a sense that it was our civic duty to make reliable information accessible to scared people. And at the beginning of April, in an already deserted Moscow, with all the bookshops and printers closed, we brought out Ancha Baranova’s Coronavirus: A Manual for Survival as an e-book (the print version will follow later). Russian people had almost stopped ordering books during self-isolation, but this book filled a need. It’s been a success. Since completing this project, I’ve stopped suffering anxiety and panic attacks, and I’ve even had several new poems inspired by the pandemic published on an American, Russian-language website, Coronaverse. And I’m working on a new novel, partly inspired (hardly a surprise) by the coronavirus.

Many thanks, Inga and Igor! Next week we speak to Evgenii Reznichenko of Russia’s Institute for Literary Translation and Clem Cecil, outgoing Director of London’s Pushkin House, about how the pandemic has affected public interest in Russian culture and literature in translation.