Sarah Gear, RusTrans PhD Student

This December, RusTrans took a momentary break from the madness of advent to attend a lively conference at the University of Glasgow. I (Sarah) spent my weekend at ‘Translation as an Act of Cultural Dialogue’, a conference held in honour of Pushkin’s 220th anniversary, organised by Drs Jamie Rann and Andrea Gullotta (Glasgow) in partnership with Institut Perevoda and the All-Russia State Library for Foreign Literature. We spent the conference listening to and taking part in discussions about Russia-Scotland literary relations, poetry, drama, and the importance and enduring relevance of Pushkin.

Irina Kirillova

Irina Kirillova

This is the first year the conference has been held in Glasgow – up until now it has taken place in the small Scottish border town of Moffat – a theme taken up by the first speaker, Professor Irina Kirillova, who answered the first question of Why Moffat? (it is indeed a very small town!) and went on to talk about the genesis of this conference and its importance in helping maintain cultural relations between Russia and Scotland. Professor Kirillova then gave the floor to Scottish poet and translator Dr Tom Hubbard, an attendee of the preceding Moffat conferences, who gave a fascinating paper on translating Pushkin’s poem Autumn into both English and Scots, focusing on Edwin Morgan’s English translation, along with Alistair Mackie’s Scots version. It is interesting to note that both of these poets decided to add a little embellishment of their own at the end of each of their translations. Tom talked about the similarities in sound between the two languages – the Scottish ‘ch’, for example, being the same as the ‘х’ in Russian – and also reminded us about the Edwin Morgan conference to be held next year in Glasgow, celebrating this prolific Scottish poet and his translations into Scots and English from many languages, Russian included.

Tom’s Russian counterpart, poet and translator Grigory Kruzhkov (whom Tom later delighted in teaching some Scots words) spoke next, about Yeats and the poet Nikolai Gumilev. He took us on a journey through Gumilev’s time in London in 1917, and talked about his meeting with W.B. Yeats – it appears he was the only Russian to meet the Irish poet. Gumilev went on to translate Yeats’ nationalist play Countess Cathleen.

Aleksandr Livergant (l) and Grigory Kruzhkov (r)

Matters came right up to date with the next talk by translator Christine Bird, who discussed her translation of Andrey Ivanov’s play, С училища, which is set in Minsk, and the challenges of bringing Belarusian dialect and swear words into English while maintaining the necessary tone – a topic that provoked lively debate about the (il)legality of putting such words on a PowerPoint presentation in Russia – and a discussion about how to carry over the shocking nature of such words, when in Scotland they have rather less power, perhaps due to their wonderfully expressive overuse…

In keeping with the theme of theatre, translator, art manager and curator Maria Kroupnik talked about the good work carried out by Class Act, a Scottish theatre initiative (transported from Scotland to Russia) that works with young children in both Scotland and Russia, with the aim of demystifying the theatre and showing kids that it is open to all, and not just a select few.

Just before the lunch break, Aleksandr Livergant, translator and long-time editor of Innostrannaya Literatura, presented on the British edition of his magazine that came out in October 2018. This came with a large feature on Scottish poets, tracking their history from the 17th century to the present day, and taking in the most famous Scottish Makars, or national poets with a varied collection of translations from Walter Scott, Burns, Hugh MacDiarmid, Norman MacCaig, Alistair Reid and Edwin Morgan, who, it was good to learn, has had his own poems translated also.

Following this, we braved the pouring rain (as a one-time resident of Glasgow I can say that Glasgow certainly lived up to its rainy reputation this weekend) and made our way to a street-food market nestling under the Gothic arches of Glasgow University. Taking shelter from the wet, we safely installed ourselves in a snug canteen in the vaults where we enjoyed lunch (while listening to carols from the university choir) and discussed the morning’s events.

Aleksandr Livergant

The afternoon session was chaired by poet and children’s’ writer Marina Boroditskaya along with Glasgow’s own Andrea Gullotta, and focused on the importance of interpretation. Aleksandr Livergant resumed the floor to talk about Nabokov’s translation of Evgenii Onegin, and the role that writer and critic Edmund Wilson played in this – trying to persuade Nabokov to work on something shorter! Indeed – the project took Nabokov 20 years to complete, and resulted in non-favourable reviews from Wilson himself.

(l-r) Irina Kirillova, Marina Boroditskaya, Grigory Kruzhkov

Dr Jamie Rann then took the conference in a deliberately surreal direction, with a discussion of Zaum poetry and Pushkin’s treatment by the Soviet avant-garde. He talked about Aleksei Kruchenykh and his experiments with sound, and Dmitrii Prigov, who rewrote all of Onegin by hand, substituting either the word безумный (mad or insane) or неземно (unearthly) for each adjective in the poem. He also talked about the Transfurists (also known as Neo-futurists, poets like Sigei, Aksel’rod, Nikonova-Tarshis) who wanted to create an international language that wouldn’t require translation – an interesting idea in a room full of translators! In essence, this discussion of Zaum brought a fourth language to the room – English, Russian and Scots being already represented.

Andrea Gullotta (l) and Jamie Rann

The University of Edinburgh’s Dr Alexandra Smith considered more canonical translations of Onegin. She discussed Nabokov and the fact that he felt that he had to translate Onegin in order to be seen as legitimate in America, and discussed his sometimes fraught relationship with Wilson. She talked about Stanley Mitchell’s 2008 translation for Penguin Classics, and also covered Charles Johnston’s 1970s translation, which it was felt provided the most natural (if not the most accurate, if we were to ask Nabokov) translation. Johnston claimed that its aim was simply to recreate the same magical feeling that he had experienced when reading Onegin for the first time in Russian. Dr Smith demonstrated that, in accordance with Lawrence Venuti’s theories on invisibility, each translator brings their own background and cultural knowledge to a translation.

Dasha Kuzina from Institut Perevoda then discussed the importance of Pushkin, and the fact that his revered status can really daunt Russian school children (who are often drilled in his verse and personal mythology from a young age) and deter them from engaging with and enjoying his work. Her solution to this is to introduce Pushkin as a real person to them – as someone who made mistakes and who lived a real life, and describe him as someone they can relate to, rather than a revered, unassailable museum piece.

After a quick coffee break, the talk left Pushkin in peace for a while to consider some other intriguing aspects and questions around Russian literary translation with a presentation from Dr Olga Allison of the University of Glasgow. Olga considered whether differences could be seen between translation choices made by male and female translators, which she did by examining different translation solutions offered for some of Lewis Carroll’s puns.

Svetlana Gorokhova, Library for Foreign Literature

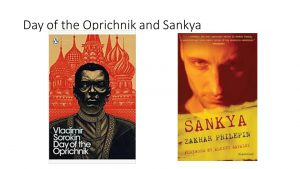

After that it was my turn, and here I moved even further away from Pushkin to consider contemporary Russian literature. I looked briefly at current translation trends, and talked about the fact that it is the smaller presses who are taking all the risks when it comes to publishing contemporary writers. I then went on to consider whether a writer’s politics affects if they are translated or not, by whom, and how their politics influences their reception in the US and the UK. To do this, I compared the reception of Day of the Oprichnik by liberal writer Vladimir Sorokin with Sankya by nationalist Zakhar Prilepin. Day of the Oprichnik has been much better received in the UK and US than Sankya, even to the point that it has entered into the literary canon via Penguin Classics, and this difference comes despite the success of both novels in Russia (in fact – Sankya could in many ways be seen as more successful). It seems that liberal authors are deemed safer to publish and promote by the big five publishing houses than nationalist writers. I ended by asking the question which will feature throughout my PhD research, namely whether we are prepared to read nationalist writers in the West, and indeed, whether we should.

Liudmila Tomanek, an independent scholar, then talked about the importance of preserving polyphonies with relation to Svetlana Alexievich’s war time accounts (many of which have, as a point of interest, been published by Penguin Classics) and Dr John Bates of Glasgow University brought us back to Pushkin when he considered the relevance of Pushkin scholarship in Poland in the 1950s, and asked to what extent academics at that time towed the party line.

The day was rounded off with a documentary by Michael Beckelhimer, Pushkin is Our Everything, that took us from Pushkin as he really was (and as described by Dasha Kuzina earlier in the day) to how he has been used by successive political regimes to represent Russia and what it means to be Russian – all themes that RusTrans can relate to! He concluded that Pushkin’s importance in Russia is vast, and he envied the fact that Russia, unlike his native America, possesses such an important poet.

Stop anyone on the street, Beckelhimer says, and they will be able to recite you a bit of Pushkin.

A huge thank you to Polina Avtonomova from the Russian State Library for Foreign Literature, and Dasha Kuzina from Institut Perevoda for providing me with photos of the event. You can read more about the conference on the Library for Foreign Literature website here.