Yes, last week was the London Book Fair and @Rustransdark, aka @CathyMcAteer1, headed along on Thursday, the last day, to attend panels and meet friends old and new. To get to them, I first had to navigate my way from country to country, weaving my way past plenty of tempting stands – China Universal Press & Publications Co. Ltd, the Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian Publishers and their accompanying Publishers’ Associations, Turkey’s impressive and alluring Ministry of Culture and Tourism, the Italian Trade Agency, the Swedish Literature Exchange, and naturally, the huge stand devoted to Indonesian literature (this year’s market focus, promoted under the superlative strap-line: 17,000 islands of imagination). A good, global effort all round.

ReadRussia stand

Tucked in the far corner, I finally found the Literary Translation Centre, the Institute for Literary Translation (Institut Perevoda), ReadRussia, and a most energetic buzz of networking translators, publishers and literary agents. There was just time for me to enjoy a quick catch up with English PEN award-winning literary translator Anna Gunin, before all eyes and ears (an eager and tightly packed audience) turned to the panel for ‘Women in Literature & Translation: Realities and Stereotypes’. This panel featured other award-winners, the literary translator, Lisa Hayden, Guzel Yakhina, the author of Zuleikha (Lisa’s latest translation), the Petersburg-based literary agent Julia Goumen, Ksenia Papazova Managing Editor from Glagoslav Publications, and panel chair, Daniel Hahn, writer, editor and translator.

Guzel Yakhina, Lisa Hayden, Julia Goumen, Daniel Hahn

The discussion started with Guzel, who introduced her latest novel in the context of the gender debate. Her protagonist Zuleikha goes on a journey of discovery, experiencing slave-like conditions as a young wife, but then metamorphoses into a stronger, more independent woman with every major life-change that comes her way. Her novel is, therefore, a triumph of women’s strength and adaptability. Guzel placed Russia in the vanguard of equal rights (women got the vote as early as 1917 in Russia, compared to as recent as 2015 in Saudi Arabia) and said that, as a female writer in Russia, she had never been discriminated against because of being a woman. Guzel’s view was endorsed by Julia, who added that the key question in Russian literary circles is not who wrote the novel, but whether the novel is a good one. Excellence will be awarded. She illustrated this view with the fact that the Yasnaya Polyana Literary Award has historically been judged by a panel of 6 men who have, in the past, championed female talent, awarding the prize to Liudmila Saraskina in 2008, Elena Katishonok in 2011, and Guzel in 2015. This is indeed impressive and yes, suggests a gender-neutral approach to selection, although I find myself wondering at what point a female writer will be allowed to take a place on the actual judging panel?

Lisa Hayden extended the theme of women’s visibility to the translation industry, remarking that, according to the stats, translated literature is predominantly a male domain and, unless women establish themselves in translation, women won’t get translated (see The Guardian, which cites research by the University of Rochester reporting that only 33.8% of translated books were by female authors in 2016, as opposed to 63.8% by men: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/aug/31/lost-to-translation-how-english-readers-miss-out-on-foreign-women-writers). The panel unanimously agreed with Daniel Hahn that translators should be mindful always of what and whom we are translating, and why. The translator is vested with the power to shape literature by decisions such as these. This discussion prompted interesting responses from the audience. One respondent working in publishing asked Julia whether there is a deliberate correlation between books which get selected for publication and the author being beautiful, young, and female in Russia? Having had a discussion up to that point which seemed generally to be breaking the usual gender stereotypes, it was a bit of a bump back down to earth to hear that yes, definitely, young, beautiful female authors look good at book launches and interviews and, consequently, sell books well. That said, as Ksenia Papazova from Glagoslav Publications rightly pointed out, you don’t have to fit these criteria to be a success in Russia: Liudmila Petrushevskaya, Liudmila Ulitskaya, and Elena Chizhova are a powerful triumvirate of stylish 60+s.

Guzel drew attention to the fact that, in Russia, 45% of senior roles are held by women – they came out top of all individual countries in a Forbes 2016 global review of senior women in the workplace. And yet, another comment from the floor highlighted a Russian paradox: namely, that whilst there may be a semblance of gender equality and impressively early suffrage in Russia, society still seems trapped in a traditional patriarchy which has been shored up by stereotypes and does not appear to be changing radically any time soon – old-fashioned chivalry coupled with rigid views of what a woman’s role should be. This, it was remarked, is one of the stark socio-cultural differences which visiting Western females notice when they arrive in everyday Russian society.

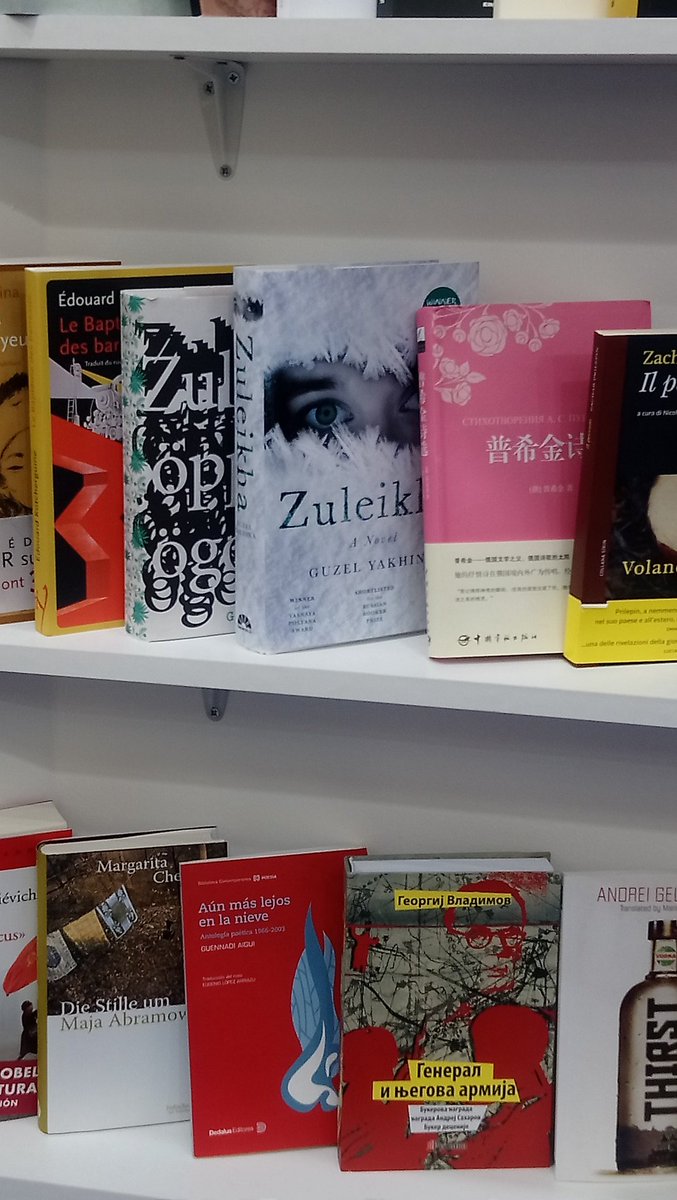

But, it seems, we in Western publishing might fall into a similar trap ourselves when it comes to book covers. The books assembled on the panel table betrayed no visual sign of gender (author or translator) except for the Anglophone version of Zuleikha, which is the only one to have a picture of beautiful female eyes looking out, tempting the reader in. It was widely thought that a distinctly “female” cover would serve as a turn-off for male readers – the jury is still out, perhaps this line of enquiry can continue here? – but, the gender anonymity of the Russian texts was generally praised by the audience as a positive move in terms of gender-neutral book promotion. Similarly, recalling the #namethetranslator campaign, it was noted by members of the audience that Lisa Hayden’s name is (most disappointingly) absent from the cover of Zuleikha, only appearing on the cover page of the book. The campaign, therefore, continues!

The panel covered a satisfyingly broad number of topics in just an hour, all of them fascinating, and skilfully steered by Daniel Hahn. There was a palpable sense of audience disappointment when it all had to come to a close. For those wanting to continue some of these themes, many returned later for one last, translation-oriented treat to end not just the day, but the whole Fair, In Conversation: Jeremy Tiang. Jeremy had an even shorter allocation, just 30 mins, but they were his alone (well nearly, discussion being prompted by Chris Gribble, Chief Executive of the National Centre for Writing). The seemingly multi-talented Jeremy, who started out as an actor, then a playwright, then a translator (http://www.jeremytiang.com/) proved himself a most entertaining raconteur too, describing all aspects of the translator’s lot – the highs and the lows, his in particular – with wit and irony. As the London Book Fair’s inaugural translator, Jeremy provided excellent advice, extolling the virtues of being part of a translators’ collective (his is the US-based Cedilla & Co., but there are others, such as the London-based Starling Bureau) in order to combat the loneliness and isolation that comes with a career in translation. Collectives not only foster solidarity, but help translators to group together to achieve maximum visibility. With visibility, comes translator validity, and with that, the hope of professionalization: translators aren’t ‘in it for scraps’, they are claiming validity as artists! The same rallying cry that translators have issued for decades and more, but Jeremy actually made it sound a plausible and attainable goal. A good message to take home at the end of a fabulous Book Fair!

Hi!

I found your blog and info about your fascinating project by accident, and I’m very glad I did!

Thank you for the interesting text on women and translation. We have a project in Finland, investigating translation and reception of women’s writing in Finland and Russia 1840-2020. Although your project does not focus on women’s writing, it will be very interesting to follow your work and publications!

Thank you!

Marja

Thank you, Marja! Do keep in touch and follow us on Twitter @Rustransdark if you can. Your own research on gender and literature looks fascinating.