In today’s post we speak to Clem Cecil, outgoing Executive Director of Pushkin House, the oldest independently funded UK charity specializing in Russian culture, founded in 1954 and (since the 2000s) located on Bloomsbury Square, London. Pushkin House has long been a focus for the the UK’s Russian-friendly cultural community, hosting art exhibitions, book launches, and talks by writers, translators, directors, and others. It even has its own bookshop! Although temporarily closed because of COVID-19, Pushkin House is offering a busy programme of online photography exhibitions and virtual tours, not to mention the exciting Facebook book club (which includes the opportunity to access Zoom talks by authors shortlisted for the annual and very prestigious Pushkin House Book Prize), and other live talks and readings including a book launch in which we’ll learn how Pushkin coped with quarantine!

In today’s post we speak to Clem Cecil, outgoing Executive Director of Pushkin House, the oldest independently funded UK charity specializing in Russian culture, founded in 1954 and (since the 2000s) located on Bloomsbury Square, London. Pushkin House has long been a focus for the the UK’s Russian-friendly cultural community, hosting art exhibitions, book launches, and talks by writers, translators, directors, and others. It even has its own bookshop! Although temporarily closed because of COVID-19, Pushkin House is offering a busy programme of online photography exhibitions and virtual tours, not to mention the exciting Facebook book club (which includes the opportunity to access Zoom talks by authors shortlisted for the annual and very prestigious Pushkin House Book Prize), and other live talks and readings including a book launch in which we’ll learn how Pushkin coped with quarantine!

Clem Cecil has been Director of Pushkin House since April 2016, and from June 2020 is leaving to work on a book about Moscow. She is former Moscow correspondent for The Times, and co-founder of the Moscow Architecture Preservation Society. She has co-edited four books on the threatened architecture of Moscow, Samara and St Petersburg. From 2012 to 2016 she was the Director of SAVE Britain’s Heritage and SAVE Europe’s Heritage.

Clem Cecil has been Director of Pushkin House since April 2016, and from June 2020 is leaving to work on a book about Moscow. She is former Moscow correspondent for The Times, and co-founder of the Moscow Architecture Preservation Society. She has co-edited four books on the threatened architecture of Moscow, Samara and St Petersburg. From 2012 to 2016 she was the Director of SAVE Britain’s Heritage and SAVE Europe’s Heritage.

Quarantine, and fear for ourselves and our loved ones, have radically re-shaped how we think and behave. How have you adapted to your new working conditions? How has the crisis affected your future plans and/or your creative process?

Pushkin House closed on the 15th March, and has furloughed half of its staff. The remaining staff are working from home. Ironically, due to online resources like Slack and Trello, in some ways the different parts of the organisation are communicating more than they did previously. So there is more synergy between our visual arts, annual book prize and music programme.

Because the house is shut, and we are an events venue, we have had to move online. We do a weekly newsletter for our Friends and subscribers. We feel it is a valuable service to provide hope, inspiration and distraction through a weekly offering put together by our team. We are now preparing for our first online events. All of our income streams have been drastically affected. We are having to change our business model as well as how we work.

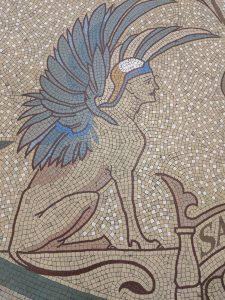

We were due to open an exhibition on 17th March – this has been postponed until the autumn but we are putting a picture a week online, with a commentary. This kind of exploration of the work is a substitute for the exhibition-related events we normally hold. We have had to shut the shutters in the house to protect the work over the long summer months.

Pushkin House, Bloomsbury

What do you think will be the knock-on effect from lockdown on translation publishing? Are there advantages as well as disadvantages for people in the creative industry?

There are always advantages as well as disadvantages. Income streams have dropped away and this is problematic for most people, but particularly artists. On the other hand this strange, suspended period is an opportunity for a different kind of experience, and reevaluation of all aspects of the creative industry – for a different perspective to arise. Some artists are enjoying the lockdown as they are able to focus on their work rather than the admin and management that is adjunct to it. Others are finding themselves unable to work at all due to the stress of it. Both perspectives are very understandable. But one thing is clear – people are turning to art, poetry, music and writing for sustenance at this challenging time. We need our artists!

What has been the impact on your work/industry of cancelled book fairs, book launches, speaker events and so on? Is there a danger that the English-speaking world will forget Russian culture?

There is no danger of that! Russian culture has the ability to inspire and fascinate in all circumstances. If anything, it will increase the hunger for it! Because the London Book Fair was cancelled we missed many of our speakers who were due to come from Russia that week and give lectures at the house. We look forward to welcoming authors as soon as travel becomes possible once more. Talks from Russian authors are important to us. They are not always as well as attended as we would like but it creates a vital link with Russian fiction and authors.

Are you aware of increased sales thanks to locked-down populations turning to books for relief? Could this be a golden moment for reading?

It is definitely a golden moment for reading. Pushkin House doesn’t produce books but we have a book shop. We are beginning to take some orders, especially related to our Book Prize. Our short list went live a couple of weeks ago and we have a created a Reading Group on Facebook. Each month in the coming 6 months, will be dedicated to one of the books on the list. We hope this year to engage with readers like never before. That is thanks to lockdown.

Thanks for speaking with us, Clem! And good luck on your next adventure! To keep up with everything Pushkin House has to offer, sign up for their weekly newsletter here. Coming soon – RusTrans interviews the Director of Russia’s Institute for Literary Translation, Evgenii Reznichenko; acclaimed translator Marian Schwartz; and the man behind the Read Russia phenomenon, Peter Kaufman! Scroll down for our previous blog posts on how the coronavirus crisis is affecting Russian culture and translation now.