Narine Abgaryan

Translator Sîan Valvis is producing the first English-language version of Russian-Armenian author Narine Abgaryan’s 2010 novel Manunia with support from a RusTrans bursary. Here she talks about the charms of translating fiction with simultaneous appeal for all ages, and Abgaryan’s talent for capturing both the grittiest aspects of her characters’ lives and their most idyllic moments. You can read part of Manunia and Me in Sîan’s translation here.

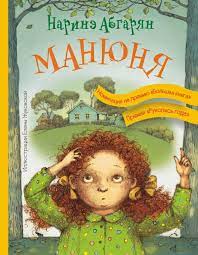

“It’s a children’s book for adults,” said my Russian friend, enthusiastically recommending Manunia and Me (my working title for Manunia). Narine Abgaryan’s autobiographical novel is the first volume in a bestselling trilogy (2010-12), detailing her wonderfully peculiar childhood in a remote town in Soviet Armenia in the 1980s. She and her best friend Manunia find themselves caught up in mishap after mishap in this upper middle-grade book about friendship. Manunia’s feisty and formidable grandmother, Ba—short for babushka —keeps an eye on both girls.

Manunia and Me is suitable for all ages, perhaps particularly YA readers. Indeed, Abgaryan’s trilogy has had tremendous success in Russian-speaking countries, largely down to the fact that parents enjoy the narrative as much as its younger readers do. Beautifully written and brilliantly funny, the trilogy has been adapted by Armenian director Arman Marutyan for a TV series currently in pre-production.

Born in 1971, Narine (pronounced Nar-ee-nay) Abgaryan is an award-winning writer, named in 2020 as ‘one of Europe’s most exciting authors’ by the Guardian newspaper. In 2016, she won the Yasnaya Polyana prize, Russia’s most prestigious literary award, for Three Apples Fell from the Sky, which was published in English by Oneworld (2020) in Lisa Hayden’s translation. (For Lisa’s own blog post in this RusTrans bursary series, see here). The Guardian called Three Apples ‘[a] magical realist story of friendship and feuds […] set in the remote Armenian mountain village of Maran, where […] an ancient telegraph wire and a perilous mountain path that even goats struggle to follow is their only connection to the outside world’. Another YA story-cycle by Abgaryan, Semyon Andreevich (2012) was named “the best children’s book of the last decade in Russia” in a report by an Armenian radio station. Her latest novel for adults, 2020’s Simon, is already being optioned for translation into English. I believe Manunia and Me could be at least equally commercially successful as Three Apples on the Anglophone market. To quote Abgaryan herself as cited in the same Guardian article: “Humanity is in dire need of hope, of kind stories.”

Each chapter sees the girls haplessly bumbling their way through life: whether it’s setting Ba’s bloomers on fire, or playing with the rag-and-bone man’s kids, who are strictly out of bounds. A bout of head-lice means the girls have their heads shaved by Ba, who accidentally dyes their scalps blue with her homemade hair-mask—though she’d have you believe it was entirely part of the plan. The girls learn a valuable lesson about life and death when they find a baby bird, fallen from its nest. And again, when they play at being snipers—complete with a real shotgun. Even when touching on controversial  themes, like death and religion, Abgaryan’s writing remains light and uplifting. With its array of oddball characters and swathes of lyrical passages, her storytelling puts me in mind of Gerald Durrell’s outrageously funny childhood memoirs, the Norwegian author Maria Parr’s children’s fiction, and the Hans Christian Andersen-award-winning Japanese writer Eiko Kadono.

themes, like death and religion, Abgaryan’s writing remains light and uplifting. With its array of oddball characters and swathes of lyrical passages, her storytelling puts me in mind of Gerald Durrell’s outrageously funny childhood memoirs, the Norwegian author Maria Parr’s children’s fiction, and the Hans Christian Andersen-award-winning Japanese writer Eiko Kadono.

Over the course of the narrative, you might get the impression that Ba was a bit of a tyrant. This is absolutely not true. Or rather, not absolutely true. […] I came face to face with this force of nature and lived to tell the tale. Kids can survive just about anything—a bit like cockroaches.

(from Manunia, Chapter One)

The narrative unfolds over the course of one long, sumptuous summer, as the girls are on the cusp of adolescence, mirroring a moment in time, just before the end of the Soviet Union. While the focus is on the girls’ antics, Abgaryan hints at the adult world just on the fringe of the girls’ awareness. The plot is set against a backdrop of characters from various cultures: Armenians, Azerbaijanis, Russians, Georgians, Romani travellers, Jews and Christians—all thrown together by circumstance, rubbing along with surprising harmony.

Translating a text with such a melting-pot of influences is not without its challenges, from sensuous descriptions of Armenian food—gata, matnakash and matsoon—to accented dialogue and specific cultural references. Capturing the girls’ speech was also tricky—Abgaryan switches seamlessly between her adult voice as she looks back in retrospect, and her child-self, blithely babbling away to her best friend. Finding the right voice for Ba was trickier still. Cantankerous at the best of times, she always seems to ‘boom’, ‘snap’ and ‘bellow’ at the girls. I found myself channelling matronly characters from old British sitcoms, hopefully imbuing Ba with the same warmth, humour and humanity as in the original.

By the end of the book, you realise that Manunia and Me is a paean for a world where, in spite of its shortcomings, children enjoy a happy, carefree life in a diverse and multicultural society. Come for the humour, stay for the touching depiction of life in the final decade of the Soviet era.

Read an extract from Sîan’s translation of Manunia here.